With Thanksgiving fast approaching, we often find ourselves becoming more introspective, reflecting on the people and things for which we are thankful. As we at Fanbase Press celebrate fandoms, this year, the Fanbase Press staff and contributors have chosen to honor their favorite fandoms, characters, or other elements of geekdom for which they are thankful, and how those areas of geekiness have shaped their lives and values.

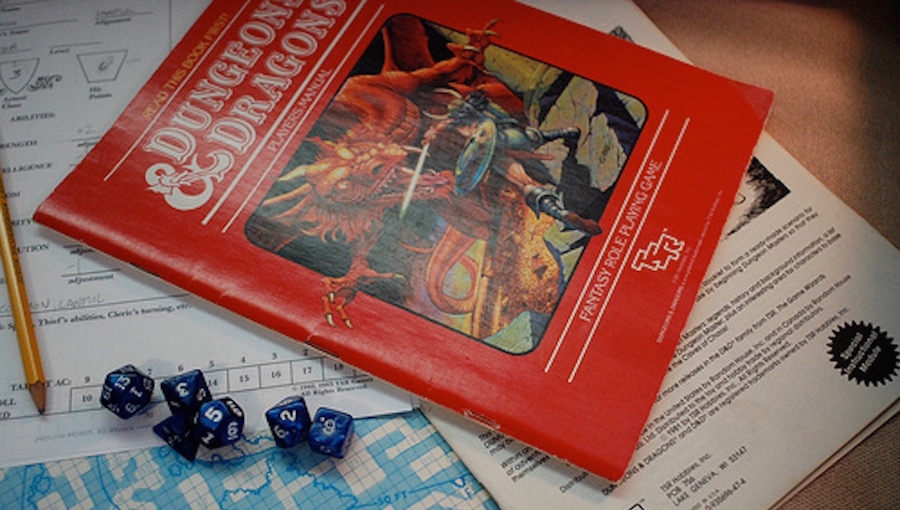

As I get older, I have a great deal for which I am thankful, but back in November 1982, I was mostly thankful for a +2 flaming swords and my Apparatus of Kwalish – man, that thing got me out of more than a couple jams, especially when the Lizard Men attacked my keep on the cliffs above the sea after my companions and I slaughtered their tribe in the swamps outside Saltmarsh over what turned out to be a total misunderstanding.

If you have any idea what I’m talking about, hello, my AD&D-playing brother and/or sister. I celebrate our shared love and mourn with you for how we have been represented in the media and perceived by our peers through the decades. Dungeons & Dragons players have been mocked since the game was introduced. Want to show that a character in your television series, book, graphic novel, or film is a geek? Have them play D&D. I’m looking at you, everyone from The Simpsons to Stranger Things. And ridicule was the best possible outcome. Pat Pulling, after the unfortunate suicide of her son, became a one-woman crusade against the game, founding B.A.D.D. (Bothered about Dungeons & Dragons, modeled after Mothers against Drunk Driving, obviously), aiming to educate parents, law enforcement, clergy, teachers, and the community at large that people who played Dungeons & Dragons were actually being taught to embrace “demonology, witchcraft, voodoo, murder, rape, blasphemy, suicide, assassination, insanity, sex perversion, homosexuality, prostitution, satanic-type rituals, gambling, barbarism, cannibalism, sadism, desecration, demon-summoning, necromantics, divination and many other teachings.”1 I think I failed to learn those teachings, because when my friends and I played, we did not do any of those things. Then, there were the books like John Coyne’s Hobgoblin or Rona Jaffee’s Mazes and Monsters, the latter made into a TV movie with Tom Hanks as a young man who thinks the game is real and nearly dies as a result, but lives on, completely insane, believing he is his character. There was The Dungeon Master, a non-fiction book about James Dallas Egbert III, who disappeared in the tunnels below his university while LARPing. (He actually had mental health issues and his disappearance had nothing to do with D&D, though you’d never know it from the book.) In pop culture, the kid who plays D&D is unable to distinguish between fantasy and reality and will eventually kill him or herself or a whole lot of other people.

Like I said, my friends and I were doing it wrong, if we believe these depictions of the game.

In all this moral panic, my friends and I simply played a game that was a great deal of fun for geeks too young to drive and not interested in just sitting around drinking or doing whatever it is teenagers were supposed to do back then.

I first learned the game from my cousins when I was in sixth grade. They helped me roll up a character. Those three were hardcore; they played with painted lead miniatures, mapped on graph paper as they went along to ensure we could find our way out, and followed rules that I think the creators of the game even thought were optional. I was hooked from that first afternoon at my grandfather’s house. I saved up my money, bought the basic set, and then for Christmas asked for the advanced books. I then became a dungeon master for my friends, and that is when the shit gets real.

Okay, not real in the Pat Pulling, James Dallas Egbert III, Mazes and Monsters sense, but real in that you commit to knowing and learning the game and to no longer having the fun of being a player – you are responsible for challenging your friends and keeping the game fun and interesting for them. I think one of the reasons I became a theatre director was because of my experience as a DM.

I am grateful to D&D and those who developed the game, as it was a gift that kept giving to our young minds. The game involves shared imagination and storytelling, which leads to what Daniel Mackey calls “the memory of imaginary events.”2 These things never happened in real life, but we remember them and laugh about them all the same. We never hit a point where we could not distinguish between reality and fantasy; the whole point of the game was that it was not reality, it was an excuse to get together and be stupid and fun and creative and re-enact the best parts of Tolkien, and then learn that you can move beyond J.R.R.R.R.R. and get really interesting.

As often as not, we didn’t take it very seriously. A typical exchange:

Kevin (DM): There is a pile of rubble at the far end of the room. Atop it sits what looks like a goblin skull.

Chris: I approach the skull.

Kevin: Okay.

Chris: I check it for traps. (rolls 37-sided die)

Kevin: You find none.

Chris: I examine the skull.

Kevin: It appears to be a normal goblin skull.

Tom: I take it as a souvenir.

Kevin: Okay. Suddenly, a ghoul comes screaming into the room. He launches himself at the half-elf.

Chris: I check him for traps. (rolls a 5-sided die)

Kevin: You find no traps but, in the meantime, the ghoul bites you. (rolls two 23-sided dice). You lose three hit points.

Tom: I take him as a souvenir. (rolls a die with too many sides to count)

Kevin: Okay. You get your sack over him, but because he is still fighting to get out, you will not be able to carry anything else.

Tom: I put the goblin skull back on the rubble.

This was an actual, honest-to-goodness conversation during the game. I remember it because we cracked up a great deal about how dumb it was. I also remember games taken much more seriously, in which we really wanted to “win.”

So, I am super-grateful to D&D. It filled hours of my teenage years, brought my friends and I closer, and gave us something harmless to do that along the way taught us to be creative and to problem-solve. It further developed my imagination and story-telling skills. Even when alone, I could sit, read the books and modules, and work on developing my own. But there is more.

I am thankful for the authority figures who not only did not find the game a threat when so much of America did, but who encouraged me to play it. From my parents, who bought me the books and put up with a group of rowdy teen boys drinking far too much caffeine and eating too many store-brand chips and salsa in their home on a regular basis. And when we weren’t at my place, the Quinns and the Grays welcomed us to be rowdy and eat like a locust horde at their places.

Mrs. Gainty, my sixth grade teacher, introduced me to her nephew when she found out I played, and he and I visited each other (He lived in another state.) several times solely to play the game. In other words, D&D brought new friends into my life. Mrs. Gainty also invited me when I was older to come back to the school for an after-school Talented and Gifted program she ran in order to teach those kids the game. Some of them became avid players.

Father Frisbee (his real name, thank you), my parish priest, came upon me reading the books at a community picnic one summer afternoon and sat down and said, “Kevin, put down the book.” I thought he was chastening me for pursuing a solitary activity in the midst of all the community, or worse, was about to tell me that for reading that D&D book I was a Hell-bound sinner. Instead, he said, “Now tell me what this game is all about. I keep hearing about it.” I explained the game as best as a 13-year-old could to a guy whom I thought knew God personally. He asked questions; I answered. We didn’t play, but I talked him through what a sample game would be like for a few minutes. After about twenty minutes, he stood back up, said thank you, wished me well, and said to “have fun – it seems like a fun game.” A year later, after mass, he pulled me aside and told me a parishioner had expressed concern that her son was playing the game, but because of his conversation with me, he told her not to worry, just, “Keep an eye on the boy.” It was the best response I could hope for.

I find players all over the place. Immediate conversation happens when I meet someone who played that first version of the game. (I fully concede I am an original AD&D fan and know nothing about 2.5, 3.0. 5.0, or 67.333 or any other version of the game. I like the one I learned on.) But when it comes up in conversation, we smile and find a moment of commonality. (When I mentioned I was writing about the game for another project, Michele, my editor at Facebase, lit up and said, “My first boyfriend was a Dungeon Master!” – a phrase that I will someday use as the title of a story.) AD&D produced a generation of people who shared experiences real (“You play D&D? You’re a wuss!”) and imaginary (“The Gelatinous Cube has begun to move towards you.”) and who are better people for it.

I haven’t played in a while, but I still have all the books, modules, dice, and (tragically) the adventures I wrote for my friends. I pull them out and look at them every once in a while and have promised myself when my kids are old enough I’m going to introduce them to the game. I’m grateful that this thing exists. It is one of the many pop culture products that made me who I am today, which has given me a world-wide community, and which filled hours with meaningful fun. If, as David Brin reminds us in The People vs. George Lucas, that our culture has made a priority of having fun and making that fun meaningful, then Gary Gygax, his collaborators, and everyone who has worked to create this thing are heroes for giving us something wonderful. I am thankful to them, everyone I have ever played D&D with, and a culture that is finally coming around to where I was in 1983. If that makes me a geek, so be it. Doesn’t matter to me – I have an Apparatus of Kwalish.

Footnotes:

- Pat Pulling with Kathy Cawthorn, The Devil’s Web (Lafayette, LA: Huntington House, 1989): 179.

- Daniel McKay, The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: A New Performing Art (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2001): 108.