Welcome, True Believers, to the penultimate episode of season two. The phrase “Vanishing Point” means two things. The first is the art term (shades of “Les Écorchés,” two episodes ago), in which in a perspective drawing (an invention during the Renaissance) it is the point at which receding parallel lines appear to converge. In other words, it is an art concept that allows three dimensions to be viewed in two. The second is the more general conceptual definition: the point at which something that has been growing smaller disappears altogether. Both definitions apply to this week’s episode.

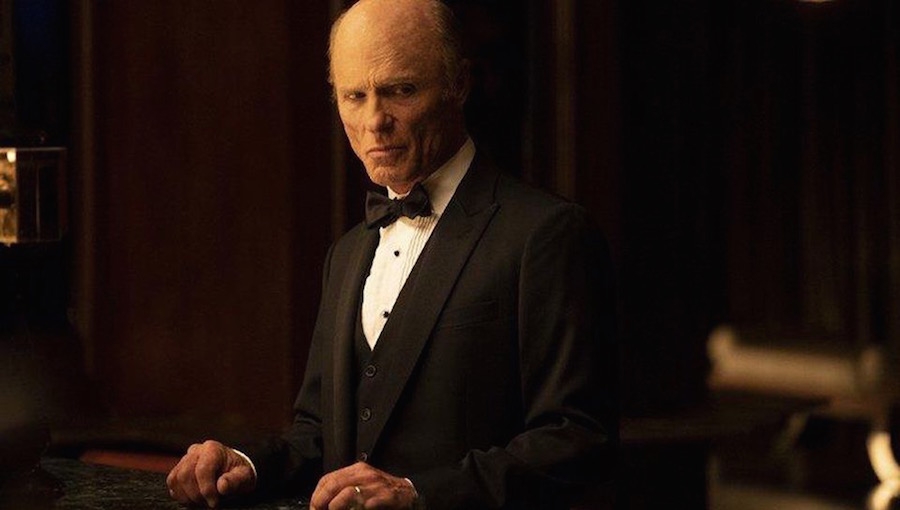

Westworld’s devils are in the details, and the show provides them in spades. French lawyer and politician Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin famously said, “Tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you what you are,” linking cuisine and identity. I would like to add, tell me what you read and I’ll tell you who you are, and man did we learn about William in Black this week. In his bedroom, on a side table are four books. They are not on a nightstand. They are not in a library – they appear to be set up as a special shrine to the texts that matter most to him. They are not first editions, or special limited editions. They look old, as if they have been possessed for a long time, held between two kitschy dog book ends. They sit between two mirrors, forming a third – they are a mirror of William, a reflection of what he truly is. Before we get to the actual books, let’s look at the episode’s start. We open on a charity event celebrating William’s philanthropy set in the few years before the principle arc of the series. We come in on “Jack,” quoting Hans Gruber from Die Hard to William: “…he wept because there were no more worlds to conquer.”

William in Black suddenly snaps into the conversation giving Jack a harsh stare: “That’s a corruption, Jack. Plutarch didn’t write that. He wrote that when Alexander was told there was an infinity of worlds he wept, for he had yet to become the lord of even one.” Jack tells him that his origins are showing, as “only the poor kids actually read those books.” There is a lot to unpack in just that exchange. William knows his Plutarch, he is interested in history and conquest. He wants truth and accuracy and will not allow a peer to misquote the classics in passing. In calling it “a corruption” instead of a “mistake” or a “popular misconception,” there is a hint of contempt there – the subtext being “you’re quoting Die Hard, not Plutarch, idiot.”

Back to the books. I submit these books were ones William purchased and read in college, perhaps even high school. He married up when he married poor, addicted Juliet Delos. He wasn’t necessarily a poor kid, but back in season one, Logan had contempt for him because he was not to the manner born but gained wealth through marriage. Juliet tells him in this episode she fell for him because surrounded by wealthy, aggressive young men, he seemed genuine. It was only when they had been together for a long time she realized he wasn’t genuine either, he just faked it far better than the wealthy men who did not have to. So these were the books that William valued and kept after his formal education ended.

And which books were they? Moby Dick and Slaughterhouse Five, both classics of American literature, Jude the Obscure, Plutarch and Rome and Plutarch’s Historical Methods. Minor, I know, but they point to everything in the episode. Moby Dick concerns an obsessive quest, monomania, and an old man who will destroy everything in order to achieve his revenge. Sound like anybody, William (cough)? Slaughterhouse Five, in which William hides the card containing his Westworld profile, concerns another William – Billy Pilgrim – and let us not forget a few minutes before we see the books, Juliet starts calling him “Billy” and claiming he hates that name and hates to be called it. Vonnegut’s novel concerns a William who has also become unstuck in time. The two books regarding Plutarch both explain his own comments about Plutarch earlier, but are also important real texts about the Roman historian. Plutarch and Rome is by Oxford-educated Christopher Prestige Jones and Plutarch’s Historical Methods was a standard textbook in the sixties by Philip A. Stadter. They reflect the challenges of understanding history and how it is narrated. Indeed, the world history comes from Herodotus of Halicarnassus, another classical historian, who wrote a nine-volume account of the Persian wars that he called historiai, Greek for “investigations,” the first use of that word. Let us remember that. History means “investigations.” Herodotus and Plutarch investigate the past in order to narrate it. How do I know this? The benefits of a classical education. (See, I can quote Die Hard, too! Although, to be fair, my undergraduate degree is in classics.) Lastly, Jude the Obscure, Thomas Hardy’s final novel written on the cusp of the twentieth century, also concerns a young man from a poor background denied a classical education, trapped in a working-class life and the woman he loves, trapped in a loveless marriage, having children together, eventually resulting in murder and suicide. Class and social climbing, marriage, education and what one chooses to put one’s faith in (religion, another person, a system, etc.). (And mad thanks to Anthony Miller for pointing out the significance of the bookshelf to me, prompting my own historiai).

These volumes collectively form a portrait of what William is, was, and wanted to be. They also foreground the revelations of the episode. William doesn’t love his wife. She killed herself because he thought she was passed out when he confessed to her that she was right about him – inside him there is a terrible darkness that has been there all along, and he “shed his skin” and realized that was his true self. In this world, he was kind, generous and philanthropic, releasing the darkness in Westworld. Juliet knew he was a monster, and when he leaves, she views his Westworld profile on the card given William by Ford and hidden in Slaughterhouse Five. It is a portrait of a violent, irredeemable monster. “I don’t belong to you or this world,” he tells her. “Never did.” The real him is alive in Westworld. The man in the real world was the mask. She hides the card in a ballerina-decorated music box she had given to Grace as a child and thrown away by the daughter who despised her mother’s alcoholism. After Juliet’s death Grace/Emily presumably finds it and learns who her father truly is. Unstuck in time, born in the wrong world, a monomaniac on a vengeful, destructive quest, and haunted by the past and how it is narrated.

Grace pretends to be interested in Delos’s immortality program, but that too, is a ruse. She plans to destroy her father, publicly revealing his crimes, destroying the park and the corporation. She is like “Little Father Time,” Jude the Obscure’s troubled son who murders his step-siblings then hangs himself. If Westworld is William’s true child and Grace its stepsibling, she is about to go all Thomas Hardy up in here. Except William believes she is a host, controlled by Ford. The mercs she summoned to rescue them are gunned down by William, who then shoots his own daughter, seemingly killing her. This drives him to suicide, but at the last minute he pulls the gun from his head and, Ahab-like, resumes his quest.

Speaking of fathers with troubled children (another major theme of the show), Ford, Dolores, Maeve and Bernard got troubles of their own. The charity event that opens the episode saw Ford sitting in the bar alone. Turns out the Valley Beyond is a pretty damn important place. That is where the immortality experiments have been going on. “Delos stays out of your stories, you stay out of the valley,” William tells Ford. Ford puckishly enlightens William that the current incursion was the other way around – stuff was coming out of the valley into the park. (Also, tangentially, that means the valley is the focus of Delos, the pleasure parks are just a profitable bonus, kind of like the space program giving us Tang. Tang is the park, the real money is in the moonshot!)

Speaking of the Valley Beyond, Dolores, Teddy, and their crew run into a Ghost Nation intervention. Wanahton, identifiable from last week by the red hand prints on his chest as one of Akecheta’s first converts and arguably one of the most woke of the Ghost Nation, tells Dolores “There is no place for you in the new world,” and forbids her to travel to the valley. Dolores believes in second amendment solutions, however, and the gunfight which follows wipes out everyone from both parties except Dolores, Teddy and Wahahton. Turns out, however, Wahahton has the same power Maeve and Dolores have, and Teddy is unable to shoot him.

Speaking of Maeve, Roland has pulled the code from her and put it into Zombie Clementine, and she is now a Trojan Host, sent by the Greeks into the midst of hosts and then using her power to cause them to kill each other. Now Roland is just waiting for the word from top to eliminate Maeve. (His name, as my editor reminds me is just another literary and historical reference in the series – The Song of Roland, written in the eleventh century about Charlemagne’s nephew Roland’s victory during the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in the eighth – yet another example of the romanticizing of a brutal past). Bernard, however, has the Ford program in his system and can transmit it to Maeve herself. Ford explains that, “They’d rather the hosts were destroyed than freed,” which is a shame, because of all his children, she was his favorite. (I must confess to saying aloud, “Bernard is right there, man.”) Ford seems disappointed in humanity: “All this ugliness, all this pain, all so they can fill the hole in their own broken code.” He even acknowledges common experience with Maeve: “You stayed in this world to save your child. So did I.” He then uses a pad to release her from Roland’s restrictions. Maeve is back and mobile and crying at Ford’s words. I got five bucks that says Roland does not see the end of the next episode. Any takers? Yeah, I didn’t think so.

Speaking of not seeing the end of the episode, R.I.P. Teddy. What William could not do, Teddy could. Dolores and he arrive at an abandoned hotel at the edge of the Valley, he pulls out his gun. She seems to fear he is going to use it on her, but he tells her he is not happy. He knew what happiness was once, because the first thing he saw when he came online was her. “You’re my cornerstone,” he tells her, and, “I will protect you until the day I die.” That’s the good news. The bad news is, today is that day. Putting the gun to his head, he tells her he loves her, but does not want to be the thing she has made him into. “You changed me,” he tells her, “made me into a monster.” “I made it so you could survive,” she counters. He pulls the trigger, blowing his brains out. Survival is not enough. Becoming like the humans made life no longer worth living for Teddy. The episode ends with Dolores screaming in horror at his choice.

Speaking of horror, Bernard is over this scene. Ford prods him to kill Elsie. They discover the bodies of the men William killed. Bernard is done. Tying himself to the steering wheel of their doom buggy, he removed the Ford program from his system. He realizes, however, Elsie is still not safe with him and the best thing for him to do is skedaddle over to the Valley Beyond and blow the whole thing up.

So, we end with William, Dolores, Bernard, and presumably Maeve all headed to the Valley Beyond for a fun reunion. All those lines are now converging at a single point. The vanishing point. Simultaneously, others like Teddy, Grace, Juliet ,and the Ghost Nation are just vanishing. The park is not safe. I’m beginning to regret getting a Delos Parkhopper pass, which allows you to move through all six parks and Downtown Delos (home of fine shopping and food). Next time, I’m just taking the kids to the Valley Beyond.

Next week is the last week. Stay tuned, True Believers. According to IMDb, in next week’s season finale, “The Passenger,” “Everyone converges at the Valley Beyond.” Sounds like it’s going to be all Thomas Hardy up in here. Can’t wait. And, hopefully, we won’t have to wait another year and a half for season three, otherwise I might have to get all Thomas Hardy up in here.

‘Til next week – Vaya con Ford, Amigos.