I remember when Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds came out. I was excited because it was hyped up around a very specific idea: that it would be taken from the point of view of the common person. No science, no government explanation, Tom Cruise would have no idea what was going on. Maybe it was because the story was familiar, but it fell entirely too short of that promise. When I experience (Because you don’t just read I Am a Hero, you experience it.) Kengo Hanazawa’s zombie epic, every step I take is with the characters it follows. Whatever they feel, I’m feeling it right along with them.

For the most part, I have no idea what’s going on in the larger scale. The bizarre things that occur are just as bizarre to our heroes as they are to me. And, at this point, those intangible ideas are so far beyond my imagination (The visual sights I’m shown and the behavior of the zombies are so foreign to me and anything I’ve experienced in zombie fiction.) that the effect of being left in the dark is an utterly thrilling and equally horrifying experience.

Maybe one reasons why War of the Worlds didn’t work is because the characters, the common person, weren’t all that well developed. You won’t find that problem in I Am a Hero. While we have no idea what the bigger picture is, we have a firm grasp of the dangers our main characters find themselves in and what their idiosyncrasies and interpersonal relationships are, even if they don’t always understand exactly what they’re up against or what exactly is going on in their own heads.

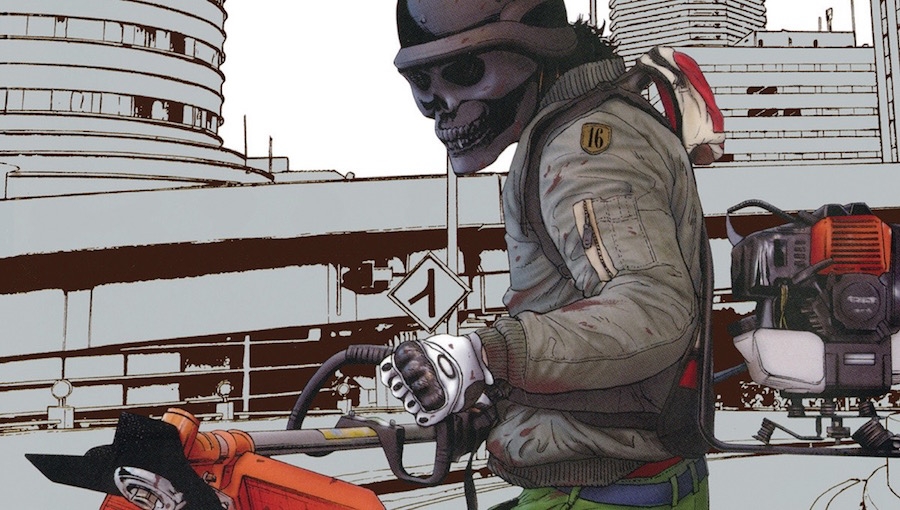

From the first issue, the main character, Hideo, has been slow to put everything together. He is a mentally troubled young man – a paranoid delusional, perhaps even on the spectrum. He’s someone who was always looked down upon, and feels treated unfairly by society, but wants to be seen as a hero. This epidemic, in a way, has given him the opportunity to be seen as a hero to other people. The sort of man-child that he is then awkwardly hopes for the hero treatment which he very rarely gets. The cool thing has been to watch him grow and change to the point in which he actually has been heroic, that we actually see the depth of his feelings towards the people around him. You pull off the awkward layers and underneath he’s a decent, caring human being. Oda and Hiromi are incredible foils to his anxious personality.

Like other good zombie stories, we explore a myriad of reactions to the epidemic at hand, splitting off on occasion to follow other characters in other groups. What makes this one great is that even the toxic characters are developed in such a way that the repression from societal restrictions are really explored. In a way, that’s a bigger theme than simple male toxicity itself. Our leads – Hideo, Hiromi, and Oda – feel guilty having to kill zombies in order to survive. They feel guilty stealing food in order to survive. It creates some genuinely funny and human moments but really does separate the good from the bad. These are characters so afraid to break from societal norms that they don’t want to regardless of the circumstances.

In this collection, Hanazawa continues turning the screws and amping up the epic scale of the events, while also devastating us on a personal, emotional level. I was reading on the subway, and I almost broke down in tears. There are moments so stirring, so surreal and beautiful, horrifying and hilarious, in this story that I would dare anyone not to be affected.

No really. I dare you. Go out and buy these Omnibuses and try not to be affected. Or buy it as a holiday gift for a horror lover you know. They will thank you for the rest of their lives. You’ll thank yourself.

Creative Team: Kengo Hanazawa (story, art), Kumar Sivasubramanian (Translation), Philip R. Simon (English adaptation), Steve Dutro (letters)

Publisher: Dark Horse

Click here to purchase.