“Between the Panels” is a monthly interview series focusing on comic book creators of all experience levels, seeking to examine not just what each individual creates, but how they go about creating it.

Certain comic artists have a style so distinct that one could identify their work from across a room. One such artist is Nir Levie, who may be the only — or certainly one of the only — professional comic book artists who is also a practicing architect. And it all started with the idea to make a graphic novel…

First off, the basics…

Your home base: Tel Aviv, Israel

Website: nirlevie.com

Social Media

Instagram: @nirlevie

Twitter: @nirlevie

Bluesky: @nirlevie.bsky.social

Fanbase Press Contributor Kevin Sharp: I ask the same first question to all guests: Why comics? What attracts you as an artistic storyteller to this medium?

Nir Levie: I’ve always drawn comics; it’s the most accessible medium for visual creators who want to tell stories. With just a pen and paper, I can create entire worlds without relying on anyone else. While writing is certainly another accessible form of storytelling, I started as an artist, so visual creation comes more naturally to me. I only began writing later on. Comics are an incredible medium because they allow for a unique blend of visual and narrative art, and it also helps that they’re relatively new. This newness opens up a lot of room for innovation and fresh ideas, which is something that excites me as a creator.

KS: Please tell readers about where you grew up and what your creative diet looked like when you were young — movies, TV, games, cartoons, etc.

NL: I grew up immersed in animation, and one of my earliest memories of drawing was a picture of Lion-O from Thundercats when I was in second grade. I remember my teachers being amazed by it, which made me realize that I had a talent for art. Batman: The Animated Series was a huge influence on me, along with Disney’s classic 2D movies like Aladdin. I was also drawn to shows like Animaniacs, particularly Freakazoid, and The Simpsons, with Futurama becoming a long-time favorite of mine.

When it came to games, I mostly played quests like Day of the Tentacle and King’s Quest, but I also enjoyed strategy games like Starcraft and Warcraft. Movies were a big part of my creative diet too, with Jurassic Park being one of my childhood favorites. I was also fascinated by Terry Gilliam’s films, especially 12 Monkeys, which have continued to inspire me throughout my creative journey.

KS: I won’t ask about the first comic you ever read, unless you recall, but what are your earliest memories of comics? Was this something you had easy access to?

NL: I don’t remember the first comic I ever read, but one of my earliest encounters with comics was with Garfield. For some reason, Garfield was incredibly popular where I grew up—we even had Garfield trading cards, which were a big deal. My real connection with comics, though, came through creating my own. As a kid, I invented a Garfield-like character named Namkury, who was a bird, and I would draw him everywhere—from school tables to walls.

My exposure to comics was more focused on European titles like Lucky Luke, Tintin, and Asterix, as I didn’t have access to the American superhero market growing up. By the time superheroes became more accessible, I had already grown more interested in literary comics like Maus, which had a significant impact on me, and Blankets. This natural progression in my exposure to comics, skipping the superhero phase, shaped me into a creator who gravitates toward more serious stories. Even when I work within genre comics, I tend to deliver them in a serious, rather than light and fun, fashion.

KS: What was it about Maus that hit you?

NL: I was completely blown away by the realization that comics could tackle such a profound subject matter. The Holocaust is a significant part of who I am as a person. My grandmother was an Auschwitz survivor and often shared her stories with me as a child. All of my grandparents were connected to this event in some way, with their families being completely wiped out. They were part of a generation that had to rebuild and create a new society, with my parents being the second generation to the Holocaust. This generational trauma is something that affects everything, even to this day.

When I read Maus, it felt like I was reading about my own family—about myself. The art, which was cartoony and simplistic, was a genius move by Spiegelman. It made the story feel accessible and gave me the belief that I could do something similar. It seemed possible.

At that time, I had somewhat lost interest in comics and was more drawn to movies and games. I was developing a specific taste for ‘weird’ stories, like Mulholland Drive and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I wanted to find comics that matched that mature, complex vibe, but I wasn’t aware of titles like Watchmen or Sandman back then. When I came across Maus, it was exactly what I was searching for—a more mature story within the comics medium. It reignited my interest in comics at a moment when I was hungry for something deeper and more profound, something that resonated with my growing interest in complex, layered narratives.

KS: When you were old enough to recognize different art styles, who were your first favorite artists?

NL: For me, it all started with Moebius—he was one of my foundational influences. After watching the movie Akira, I was captivated by Otomo’s work, especially his cityscapes and background details, which were awe-inspiring. This led me to discover Geof Darrow, whose art I became obsessed with. I spent a lot of time studying the way he portrayed details. I was also drawn to Tomer Hanuka, particularly for his approach to coloring and his ability to create impactful compositions for covers.

KS: How about anyone outside of comics?

NL: I was deeply inspired by classical painters like Michelangelo and Rembrandt. I never really connected with modern art; I was always more drawn to older works. Artists like Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Lucian Freud, and Francis Bacon fascinated me, especially their intriguing depictions of anatomy. For me, comics are all about anatomy, much like classical art, where the human body is a central subject. This is especially true in the superhero genre, where the focus on anatomy is very similar.

KS: Moving to you as a creator, what kinds of art did you enjoy making as a kid? Was it a hobby you practiced from an early age or something you came to later?

NL: From a very young age, I was captivated by the idea of creating stories and characters. I vividly remember being drawn to the world of comic strips, where I would invent characters with funny and light-hearted vibes. These comic strip characters were a big part of my early creative expression, and I loved bringing them to life on paper. My passion for storytelling didn’t stop there, though. I was equally fascinated by animation. Back then, the technology was fairly basic, but I spent countless hours experimenting with traditional and digital animations using the early software that was available.

My brother and I often collaborated on these projects, which added another layer of creativity and fun. We’d create short animated clips, funny sketches, and even simple games. It was an incredibly organic process—there was no formal training or structured approach; it was just us exploring and having fun with the tools we had. This creativity was something that developed naturally and was a big part of my life from a very young age.

However, as I got older and entered high school, my focus started to shift. I found myself creating fewer characters, and although I continued to draw and doodle, it wasn’t with the same sequential storytelling focus as before. I was still connected to art, but it became more about individual drawings and less about creating narratives.

KS: You mentioned earlier that you’ve always made comics, but what did those look like? For example, was Namkury ever in a sequential story situation?

NL: Oh, it was definitely sequential. I created short, one-page comics with Namkury, placing him in various story situations rather than just static images. My mother actually kept some of these comics, and she recently found a few of them. It was an incredible experience to rediscover those early creations—it reminded me that I’ve been working in the same medium my entire life.

I think this really gets to the heart of what makes comics so special. Comics are a medium that anyone can access and create, no matter their age. When I was making those comics as a kid, no one could stop me. I didn’t need permission from adults, and I didn’t require any special tools—just paper, a pen, and my imagination. That’s the beauty of comics: They’re a visual storytelling medium that’s open to everyone, whether you’re 8 years old or 80.

But the trick isn’t just making comics—that’s the easy part, and anyone can do it. The real challenge is to create groundbreaking, innovative, and excellent comics. That’s a job only a few can accomplish, and it’s a goal I’m constantly striving toward in my own work.

KS: Do you recall when you thought of pursuing art as a career path? Was it one “a-ha” moment or an idea that had been simmering?

NL: There were definitely moments that made me realize I might do something more serious with my art. One of the earliest was before I went to university, during a trip to India with friends. While we were there, I filled a sketchbook with various artworks—some were landscape drawings, others were sketches, but I also created a short comic related to the trip, around 20 pages or so. I’m not sure if I thought of pursuing art as a career when I was creating it, but looking back, it was a significant step towards taking my art more seriously.

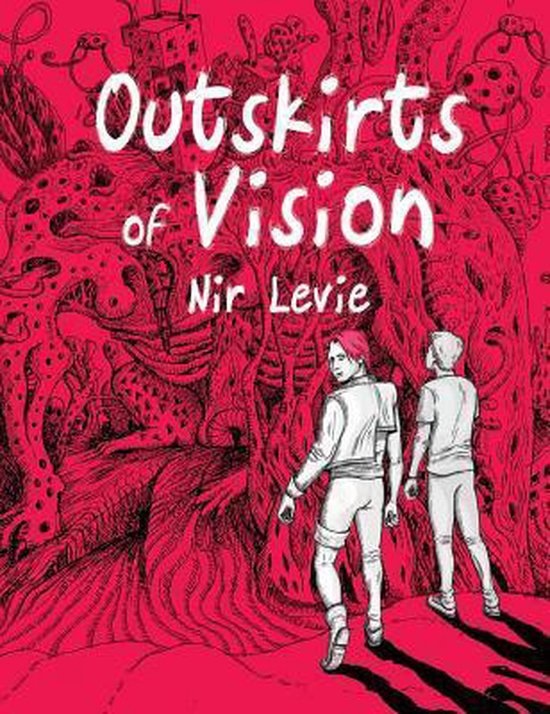

The next key moment came during architecture school. I studied architecture and am a practicing licensed architect now, but as a student, I was constantly drawing. I made short comics to explain my architectural designs and also created surreal cityscapes and weird, amorphous architecture. I remember my friends encouraging me, saying I had to do something with these drawings. After finishing school and starting my career as an architect, I decided to take all these drawings and weave them into a story, which became my first graphic novel, Outskirts of Vision.

Of course, I made the common mistake of making my first work an epic 250-page comic, so it took some time to finish. After I couldn’t find a traditional publisher for it, I decided to self-publish it in 2014. That experience really solidified my commitment to pursuing art as a career path.

KS: Obviously, the market has changed since 2014, but if current you could give the Nir of back then some advice about that book to make his life / publishing journey easier, what would you tell him?

NL: I would probably start by telling myself to make it shorter. Failing faster is one of the best pieces of advice I can give to artists starting out in the comic industry. The longer the project, the more time you’re spending on something that could ultimately serve as a learning experience rather than a finished product.

The second thing I’d say is to not bother looking for a publisher for the first work. In the current market, I believe your first project should be self-published. No matter the quality of your work, it’s almost impossible to find a publisher at that stage. That initial work is more about learning and building momentum than about getting a major deal.

Third, and related to that, I’d tell myself not to view the comic as a standalone entity. It’s a stepping stone to the next thing. As soon as you finish, start working on your next project. The process of moving forward is organic—you’ll naturally implement the lessons you’ve learned into the next work. But when you’re just starting out, it’s easy to become too possessive of your first creation. You have to learn to be more flexible. Once you finish and self-publish it, let it go and move on. That’s part of the growth process.

KS: What was the first time you ever got paid for making art?

NL: I didn’t get paid for it, but when I was 15, I was part of the team that created our class yearbook. I drew caricatures of every kid and worked on the cover of the book. The teachers even took me to a graphic designer’s studio, which was a big deal for me at the time. It gave me a chance to peek into a professional working environment, and it was an eye-opening experience.

Later on, I did get paid for my art when I worked as a caricaturist at a convention. There, I was paid to draw people’s likenesses, which was a new experience for me. During my time as a student, I took on more caricature work, designing them for weddings and running a small graphic design business. However, I quickly realized that I didn’t enjoy it. The couples were often very particular about how they wanted to be drawn, and I found that most people don’t actually like caricatures of themselves, especially for something as personal as a wedding. They wanted to be depicted in a way that closely resembled their actual appearance, rather than in an exaggerated, caricature style. That experience left a lasting impression on me, and to this day, I’m not particularly fond of drawing likenesses of specific people. However, I still practice this skill in live drawing sessions with models, as I believe it’s important to keep improving, even in areas that aren’t my favorite.

KS: What did your comics journey look like after publishing Outskirts, especially in terms of how you positioned yourself to advance in the field?

NL: I decided that for my next comic, I wanted to approach it in a more structured and thoughtful way. With Outskirts, the process was almost reversed—I created the images first and then connected them with a story later. For my next project, I wanted to start with the script and then work on the art. I began actively reading about comic scripting and writing, studying other comics of the time to improve my storytelling.

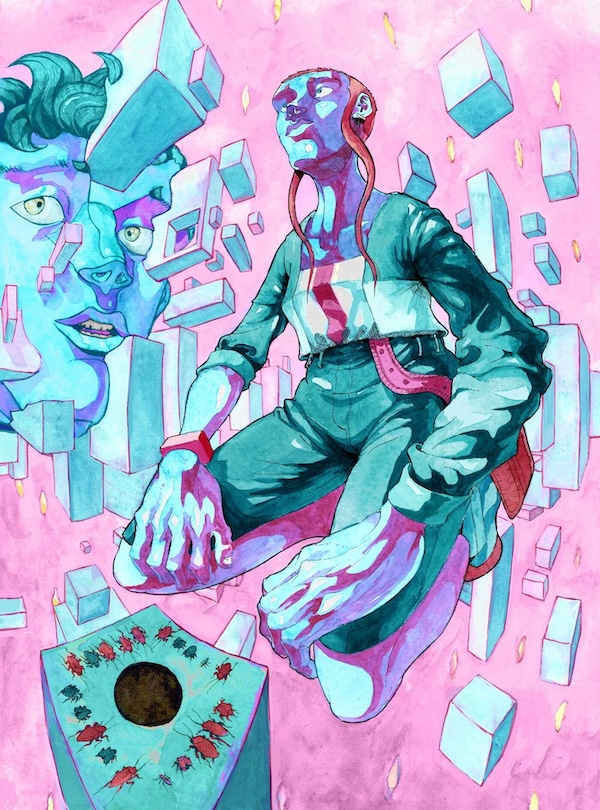

As for the art, I kept a balance between traditional and digital. I still drew backgrounds and landscapes traditionally, while the character work and sequential storytelling were more digital. In this project, I experimented with a POV style, which I believe came from the themes of the book, which explored consciousness and identity.

But, once again, I made the mistake of tackling an epic—I ended up with a 300-page story. At the time, I thought that to improve on Outskirts, I needed everything to be bigger and better: better scripting, better art, and longer. Eventually, I found a publisher for the project, Mycelium Seep, through Markosia, a small UK-based publisher that ended up being the best fit. They divided the story into three graphic novels, which became my second major project. It also opened doors for me, leading to interviews on larger platforms and some success in the industry.

KS: Your art is so distinctive and easy to tell apart from other comics on the shelves. Are there any artists you can point to as direct influences on your development, aside from being names you admire as a fan?

NL: First, I’m always actively striving to differentiate myself from other current working artists. While I study the work of other artists, I make it a point not to imitate how they draw things. Instead, I always ask myself if there’s a different way I can achieve the same result. It’s a harder and slower process, but I tend to be contrary by nature—I’m always looking for a different path. This contrarian approach, I think, is what has led my art to become distinctive. There’s nothing wrong with borrowing techniques or ideas from other artists, but for me, finding my own way is key.

As for specific influences, I’ve mentioned Moebius, Otomo, Geof Darrow, and Tomer Hanuka as having a direct impact on my development. Their work has been foundational. I’ve also been blown away by James Harren, Sean Gordon Murphy, and Paul Pope. Later in my journey, I started looking for inspiration from earlier illustrators, and that’s where I discovered E.M. Lilien, a Polish-Jewish Art Nouveau illustrator and printmaker. His work, especially around Jewish themes, was a big influence and led me to explore other Art Nouveau artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Egon Schiele.

In terms of storytelling, my biggest influences have been filmmakers like David Lynch and Terry Gilliam. Their ability to weave surreal and complex narratives had a profound effect on me. I also admire the works of Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, and Grant Morrison, and later I found inspiration in Howard Chaykin and Howard Cruse. The list could go on, but these are the key figures who have shaped my artistic and storytelling sensibilities.

KS: Was there ever pressure — internal or external — to steer your style in a more traditional direction?

NL: I think this pressure is always there organically. There isn’t a specific person or entity telling you directly to be more mainstream, but there’s a part of the industry—especially the superhero market—that subtly hints at drawing you in that direction. The Big Two have shaped the comic industry as it is today, and a big part of that is their style of drawing characters. There’s nothing wrong with this at all; they’ve paved the way for the comic landscape we have now. Of course, even within that space, there’s a huge diversity of styles, from Jack Kirby to Jim Lee, and contemporary works have taken it even further.

For me, though, I didn’t start out wanting to make money from comics. I had a job as an architect, so that side of things was covered. From my first project up until now, I’ve balanced architecture and comics, reducing the amount of time I spend on architecture as my comics career progressed. I knew that if I wanted to be successful in the superhero market, I would need to adapt my style to fit that space.

The only time I received direct criticism on this was during a meeting with an important figure at one of the Big Two publishers. They told me they loved my style, but it was more suited for a European publisher. While they didn’t have a ‘house style,’ they knew what wasn’t a fit for them.

That said, I’m starting to see more daring work even with the bigger publishers. Artists like Tradd Moore with Silver Surfer Black and Doctor Strange, or Matias Bergara with Immortal Hulk, are pushing boundaries. I believe that in order to stand out with your own work, you have to differentiate yourself from others, and that’s the approach I’ve always taken.

KS: Hypothetical question: Imagine I can hook you up to a machine like in The Matrix and immediately upload a new expert-level skill into your brain. This can be something you’re OK at now but want to be better, or something you have no aptitude for at all but wish you did. What’s your new expertise?

NL: I would definitely choose something I’m not good at—something that’s the opposite of what I naturally gravitate toward. It would have to be a business-related skill, like mastering the stock market. With that expertise, I could make enough money to support my comic career and gain the freedom to create art on my own terms, free from the constraints of capitalism.

I have a lot of criticism toward capitalism because I think it organically favors certain attributes and shapes our society in a way that has evolved into a kind of perversion of the original idea. In my view, to live happily, you need to release yourself from the system you’re a part of. Unfortunately, in a capitalist society, the way to do that is by making a lot of money.

The reality of the comics industry right now is that it’s hard to make a sustainable living unless you’re working with the bigger publishers or you’re very famous. So, being able to make money in a different way would give me the freedom to focus on creating art as I please.

KS: What’s a comic title you’d point to as an example of this medium at its very best? Something that offers the “whole package” as far as you’re concerned…

NL: My answer would have to be Akira. There are plenty of other comics that rank highly for me, but none of them excel in both the art and story as seamlessly as Akira. It’s truly a masterpiece. In terms of art, I’d point to The Incal by Moebius as a standout. The visuals are breathtaking, and it’s one of the most influential works in the medium, especially in terms of world-building and imaginative design. When it comes to story, From Hell by Alan Moore is another example of excellence. Its depth, complexity, and the way it weaves history with fiction is unparalleled.

But Akira merges both elements—art and story—like no other. Otomo’s detailed cityscapes, his masterful use of perspective, and the sheer dynamism of his action sequences are extraordinary. At the same time, the narrative is so rich and multilayered, exploring themes of power, corruption, and humanity’s future in a post-apocalyptic world. It’s the perfect balance of storytelling and visual artistry, and for me, it represents the pinnacle of what the comic medium can achieve.

KS: As we wrap up, please let readers know what you have out now and/or upcoming that they should be on the lookout for.

NL: Right now, I’m working on a mini-series for a new publisher called Panick. It’s a horror sci-fi publisher founded by Kris Longo, whom I know from Heavy Metal, along with other industry veterans. The project was announced at San Diego Comic-Con, so I can share a little about it. The series, called Razor Gray, follows an ambitious architect who must confront the consequences of his curiosity while investigating mysterious alien relics found on the planet Ceres. It’s a sci-fi archaeological adventure that explores Plato’s parable of the cave, giving glimpses of higher dimensions just beyond the characters’ reach. Their journey has the potential to change the future of humanity as a whole.

I’m also excited to be working on my first collaboration with a writer, as well as an illustration project for a well-known musician, though I can’t share details on either of those yet.

If you’d like to meet me in person, I’ll be at the Orlando Art Expo [January 2025]. It’s a newer show that focuses on original art, and I’ll be there with my art rep selling original pieces. I’ll also be open for pre-show commissions, so stay tuned for updates!