“Between the Panels” is a monthly interview series focusing on comic book creators of all experience levels, seeking to examine not just what each individual creates, but how they go about creating it.

For someone with ambitions of breaking into the American comics business, living in the Netherlands before the internet explosion may have made that seem like an unlikely – if not unreachable – goal. Dennis Menheere, however, is an example of not taking one’s eye off the prize. Fast forward years later and Dennis has not only reached that goal, but had his work represented in comics by multiple publishers.

First off, the basics…

Your specialties (artist/writer/letterer/inker/etc.): Artist

Your home base: Netherlands

Website: dennismenheere.com

Social Media

Instagram: @dennismenheere

Twitter: @dennishmenheere

Bluesky: @dennishmenheere

Fanbase Press Contributor Kevin Sharp: Why comics? For an illustrator, what’s the appeal for you of this medium specifically?

Dennis Menheere: To me, from an artistic standpoint, comic books have it all. Making comics challenges an artist to learn from their mistakes, constantly improve and find new ways to engage with readers. It encompasses every genre known to man and every and all artistic technique can be used to convey a story. It’s a cliché but I truly feel one’s imagination is the only limit when it comes to comics.

KS: Was art something you did regularly in your younger years or something you came to later?

DM: My family tells me I have always drawn, at all times, everywhere. At family get-togethers, I sat in the corner with my blank sketchbook and doodled. I used to tape X-Men TAS episodes, pause said tape, and try to draw the stills shown on my TV. At school, all my books were filled with drawings, front to back. Drawing stuff was just always something I enjoyed more than anything else. Still is.

KS: Would that show have been your first exposure to the X-Men?

DM: I had a few ’80s X-Men books featuring the classic ‘Giant-Size’ Line-up. My first time seeing any X-characters was Infinity Gauntlet and the OG Secret Wars. But TAS was my first exposure to the Blue and Gold X-Men. To this day, whenever I read X-Men, I still hear that show’s voice actors in my head!

KS: What was the comics scene like where you grew up, as far as being a young reader? Did you have easy access to the material, either through newspapers, “floppies”, webcomics…?

DM: There was no comics scene in the Netherlands. There were translated comics, thankfully, and my parents occasionally got those for me, but that was just a small fraction of what was out there. Nobody I knew read non-Franco-Belgian comics, which I love as well, apart from my friend Alex whom I met at high school. I had a paper route when I was 12 or 13, and every month I took my sweet paperboy money and took a train to a city 45 minutes from my home, where they sold actual untranslated US comics. The owner of the store didn’t allow customers to open up their bagged floppies, so I picked my comics by cover and got my news from sporadic Wizard mags. Thanks to those covers, Chris Bachalo is still one my favorite artists to this day and I still own those comics. They’re treasures to me.

KS: Were you able to follow favorite artists at all back then?

DM: I collected whatever title I could, and discovered artists as I went. For me, the ability to actually find artists’ books didn’t actually exist before online shopping. When I got a little bit older, I visited shops around the country and discovered new books and artists and publishers. I had never seen a [Mike] Mignola book until I found one in a shop 4 hours from my house and was immediately hooked.

KS: Roughly when did the idea of an artistic career occur to you? Was it an “a-ha” moment of inspiration or something that had simmered for a while?

DM: I’d say it was reading my first batch of translated ’70s Marvel comic books that my uncle gave to me. Our editions of Spider-Man comics were complemented by other miniseries, like Moon Knight or issues of Silver Surfer, Defenders, and New Mutants. I was in love with comics as an artistic medium and intrinsically felt like that was the thing I was going to be passionate about, although I couldn’t vocalize it back then. I never stopped illustrating, and while I developed my skills over the years I got some commissions from my local band scene. An album cover here, a t-shirt design there. Apparently, people were willing to pay for my work. It was then my brain decided that, someday, this would be ‘what I do for a living’.

KS: Do you remember when you first got paid for a piece of art?

DM: I was asked to do some art for our school paper at age 13 or something. It was ten bucks but it was pretty cool. Ten bucks for doing the thing I enjoy most!

KS: Once you decided art was what you wanted to do “for real,” what were the next steps you took to pursue that?

DM: I initially wanted to go to art school but I couldn’t afford it, so I bought a bunch of educational books on anatomy and composition, and taught myself color theory by looking at a lot of Klimt, Monet, and Mucha — and reading thousands of comics. I started getting freelance art gigs in my regional music scene and built my portfolio. Eventually, despite not having any art degree, I landed jobs in the creative field, doing illustrations for packaging and t-shirts, all the while taking on freelance work and selling silkscreen prints, until I decided to pursue my boyhood dream of being a comic book artist.

KS: How did your family feel about this dream of yours? I know many parents might look at art as a hobby rather than a career.

DM: I come from a family of hard workers, which eventually had a good effect on my work ethic. They did support me to a certain degree, and they did acknowledge my passion. They did however always warn me that art is not a surefire way to make a living and a regular ol’ job is a safer choice. In all honesty, I think I’d tell my daughter the same. I can’t really deny the fact.

KS: Did you have notions of ways to break into the comics business?

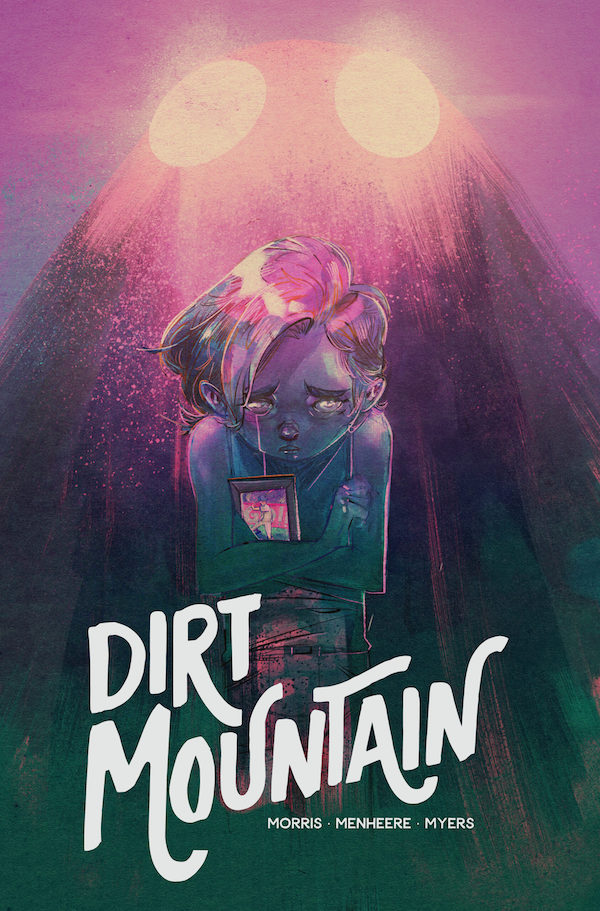

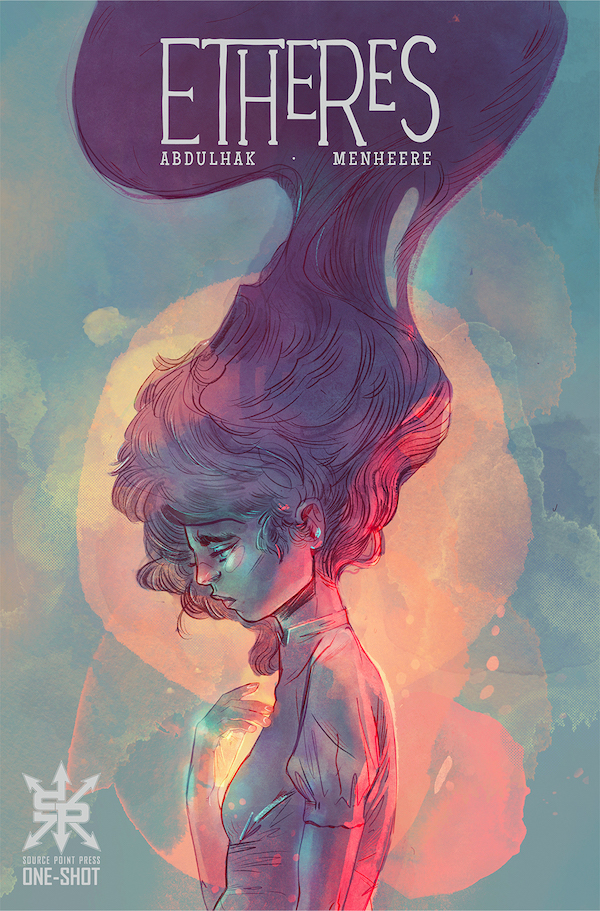

DM: As a teenager, the notion of getting into US comics was not feasible at that time. This is pre-internet so the idea of getting noticed there – or even auditioning– was just not going to happen seeing as I wasn’t even from the US and there was no clear information as to how to even approach a publisher. That all changed with social media and the growth of the internet as a whole. The world was smaller now. I had worked as a commercial illustrator and as a graphic designer and even did some 3D modeling for a while, but it never satisfied. After some pretty drastic personal life-stuff, I decided to go for it. I met Anas online and we created our book, Etheres.

KS: What made you and Anas decide you’d like to try actually making something together? What clicked between the two of you?

DM: After deciding to fully get into comics, I made a really underwhelming post about looking for comic-related work in a Facebook group which aims to connect comic artists and writers. I didn’t add any pictures, just a link to my Instagram page and something along the lines of “Hey, uh, who wants to make comics with me?”

Anas took the leap and contacted me, and we agreed to do a book together. We worked on Etheres and talked on a daily basis, developing a close friendship along the way. Anas’s gut-punching writing pulled me right in and continues to do so with every work they pen. Other than that, we’re just kindred spirits with a lot of similar – as well as extremely dissimilar – tastes and opinions, and a camaraderie that blooms out of the dream to ‘make it in comics’ as outsiders together, even though we come from vastly different backgrounds.

KS: Once you got going on the book, how were you both thinking about the next steps for the project? It was eventually put out through Source Point, but what was the path to get to them?

DM: While working on the book, we discussed pitching it as we felt we might have a small shot at getting it on shelves. We looked at all the publishers that were open to submissions, eliminating the ones that didn’t publish one–shots. Anas wrote a convincing pitch and mailed each and every one of them. Nobody actually replied, because we were just two unproven bozos, I suppose, but luckily Source Point picked us up. There’s no secret ingredient here; we didn’t have a massive following or any hype whatsoever. We just tried to make a quality book and hope for the best.

KS: Looking back at that whole process leading up to being published, what lessons did you learn about the making of and/or business of comics?

DM: We mostly learned that getting published as basically nobodies in the industry is nigh impossible. We didn’t know anything about anything. The industry isn’t at all transparent about the workings of comic publishing, and the money that’s involved in doing so. And we didn’t care either, we just really wanted to get a book out on shelves. Our shared dream to have a comic book available on international comic book shops was something so farfetched, and, honestly, it’s still hard to pinpoint why it worked. But we remained positive and we cheered each other up whenever things looked down. But, to be a little more pragmatic: to increase your chances you need a good pitch, have a cover, have enough finished pages – lettered if possible – and have a lot of patience.

KS: Any advice you’d offer the Dennis who was working on the book back then to make his life a little easier?

DM: I’d tell myself to not be so finicky and probably to use underpaintings. I’d also love to tell myself that all this hard work is actually going to pay off.

KS: If an art career had never worked out, what would be an acceptable Plan B profession where you could imagine yourself being at least content?

DM: Sheesh, good question. I’d probably take up an actual education and do something science-y or be a librarian or something stuffy like that. Maybe open up a record store? I’ve had many jobs and I honestly don’t even want to imagine myself doing anything else at this point.

KS: Imagine you can spend a day inside the studio of any artist from comics history, hanging out, watching them work, getting coffee, whatever they needed. Who would be your pick and what would you hope to get out of the experience?

DM: I admire a whole lot of artists, old and new, but I’m going to say Bill Sienkiewicz. I’d love to be a fly on the wall watching him work, and pick his brain a bit. He’s one of those artists that has always had his own recognizable style, which is a quality I value greatly in comic artists, and I feel that must have been a risky, yet conscious, choice which in the end paid off. This might be conjecture on my part, but for me that is really inspiring.

KS: In your experience, what’s one word you think is a necessary trait for being successful in comics?

DM: I can’t really pick just one but I’m going to go with discipline. The discipline to improve, to get off your ass and do the work, to not get distracted by the nonsense, to promote your work, to sacrifice your time and suffer through all of it. Comics is hard.

KS: Comic Book Hall of Fame: Please pick one title you would induct as an example of the medium at its finest. Why that pick?

DM: Also impossible and very subjective I suppose. Just one? Okay, today my pick is Sandman: Overture by Gaiman, Williams III, and Stewart. It has a great mix of modernized mythology via the Sandman universe, the kind of quirky weirdness you can only get in comics, some of the best art you’ll ever see – those De Luca panels are mesmerizing – and expert, moody yet explosive coloring by my favorite colorist, Dave Stewart. It’s top notch.

Also, Saga.

KS: Finally, please let readers know what you have out now and what you have coming out this year.

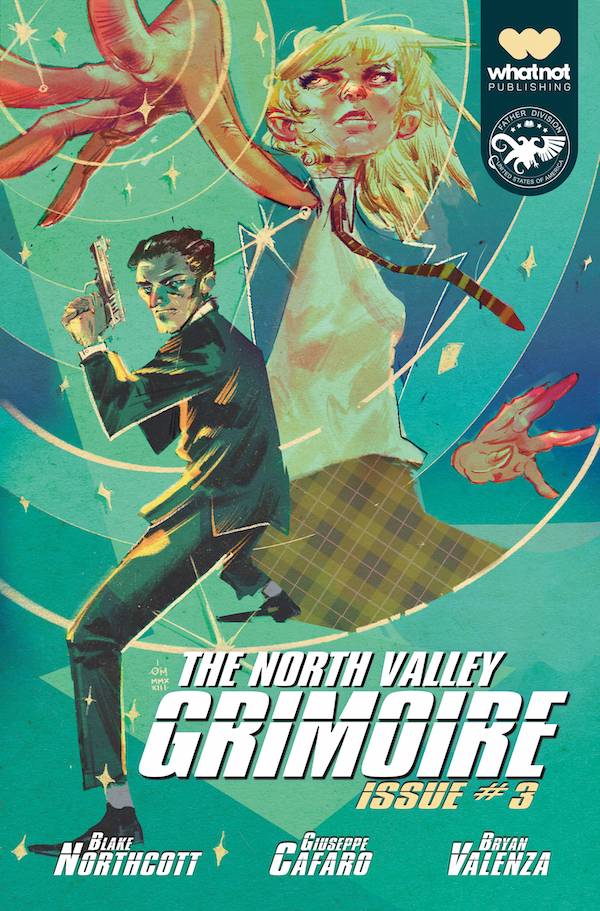

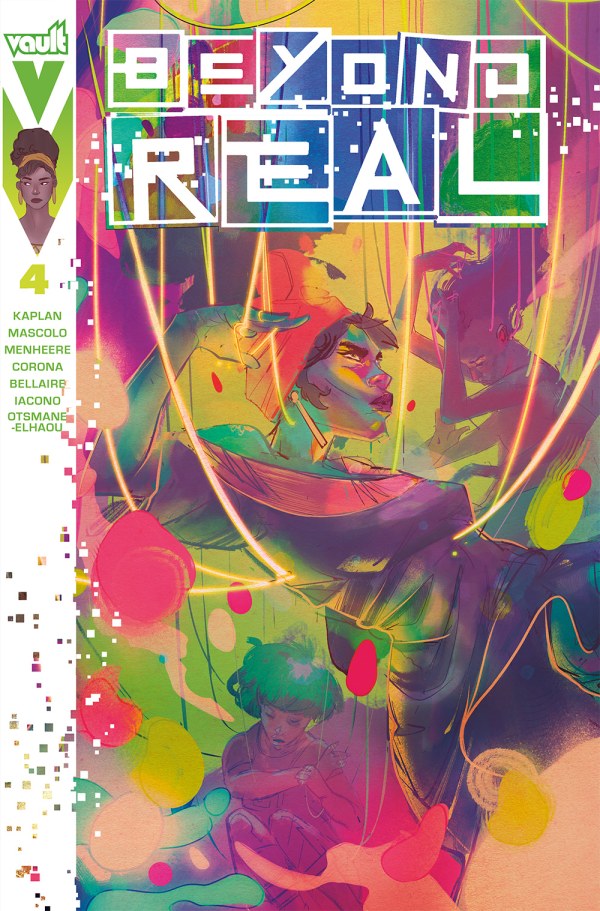

DM: Beyond Real is out from Vault Comics, which I did a chunk for amongst an amazing team, the Stardust Anthology is coming fairly soon, and I just finished my first work for Image Comics with a cover for Wes Craig’s Kaya series. There’s also two projects I’m not allowed to discuss, and I will be pitching another story with Anas this year, as well. Lots of stuff.