“Between the Panels” is a bi-weekly interview series focusing on comic book creators of all experience levels, seeking to examine not just what each individual creates, but how they go about creating it.

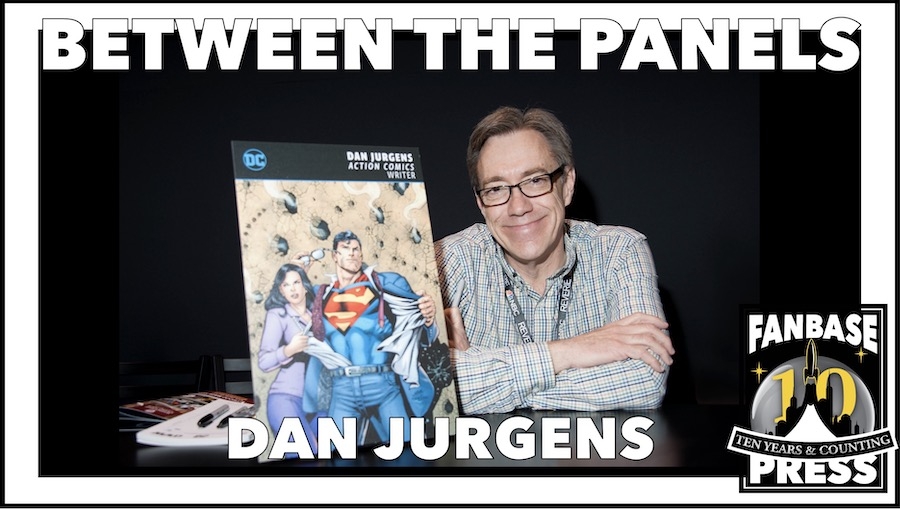

For longtime comics readers, Dan Jurgens really needs no introduction. He’s illustrated and/or written just about every major superhero character, created his own (Booster Gold), and was a guiding force on one of the biggest events in industry history (The Death of Superman). Dan is not only an icon, but one of the most open, approachable pros in the business.

First, the particulars…

Your specialties (artist/writer/letterer/inker/etc).: Artist/Writer

Your home base: Minnesota

Website: www.danjurgens.com

Social Media

Twitter: @thedanjurgens

Current project titles:

Batman Beyond (DC)

Nightwing (DC)

Fanbase Press Contributor Kevin Sharp: Of all the artforms out there, what attracts you specifically to working in comics?

Dan Jurgens: It’s because there’s no story you can’t tell. I term myself a storyteller. In comics, if you want to do a story that’s a “locked room mystery,” you can do that. If you want to tell a horror story, or something that takes place in a different universe, you can do those. It’s a tremendously elastic medium for being able to tell a story as big as the cosmos, or as small as something that affects someone on a very personal level.

KS: Fanbase Press launched the #StoriesMatter initiative this year to highlight the impact that stories can have on their audience. When you think back on the first stories that really had an impact on you as a reader, do any especially stand out?

DJ: Sometimes, it’s imagery that’s stuck with me, and other times it’s the story. For example, I was a fan of the Adam West/Burt Ward Batman. That was all I knew about superheroes. Then, one hot summer night, I was walking through the neighborhood and there were a couple of older kids I knew sitting out on their stoop, and they had comic books. I had no idea these existed. I remember distinctly, one of them pulled out an old Batman comic [#156] with the famous “Robin Dies at Dawn” cover. I saw that and thought, “They killed Robin? That can’t be — I see him on TV!”

In terms of stories, it was some of the first ones Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams did with Batman. Or “Kryptonite Nevermore” in Superman. Or the Manhunter series by Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson, which to me is one of the greatest arcs in comics.

KS: When you’d read more comics and were old enough to differentiate among artists, who were your first favorites?

DJ: The first one I really recognized as being different was Neal Adams. I was primarily a DC reader at that time, so it was Adams, Curt Swan, and Gil Kane. After I started picking up Marvel, I discovered Jack Kirby and John Buscema. I started trying to figure out why these artists were different and what I liked about each of them. For example, Kirby was the “blocky guy” because his figures had such mass; Gil Kane was the “liquid guy” because his figures were so fluid.

KS: What’s the first “real” art project of your own you remember? I’m looking for something that felt like a serious project for you, wherever you were in your artistic development and whether or not you anyone else ever saw it.

DJ: I was always drawing as a kid. In third grade, everyone in the class had to do a self-portrait. They all got hung up on the blackboard after, and I remember that mine was really different. My next thought was, “Because it’s way better.” That’s when I realized: It wasn’t just me sitting at my kitchen table drawing, [but] I was doing it at a higher level than anyone else in my class. It was me recognizing the difference that was already there.

KS: To jump forward, your first pro comics gig was in Mike Grell’s Warlord?

DJ: Yep, that’s right. At that time, I was already working as a graphic designer and doing well. Comics were something I’d always been interested in; in my spare time, I’d doodle up various pieces for a portfolio. [Warlord creator] Mike Grell was making an appearance at a comic store in town, and I stopped in to show him my work. At that point, he was only writing the comic; he told me they were looking for a different artist and suggested I send my stuff to the editor. They gave me and another artist each five test pages. They picked me, and my first issue was Warlord #63.

KS: Was there any sense of “A-ha, I’ve made it!” when that assignment landed?

DJ: I was doing it at night — I didn’t quit my day job, because I did not have that sense. I thought I’d work in comics for a couple of years and then step back and go get a real job again. There are times when — and I think this is common in creative fields — where even now I can say I’ve never had that “A-ha” feeling. In order to get better, you’re always have to find fault with your own work.

KS: So, looking back at your artwork from your earliest years in comics, what’s something that stands out as different from the work you produce now?

DJ: Storytelling is a strong part of it. There are techniques I use now that I didn’t use then; I look back and see an awful lot of my mistakes in that area. Early on, I’d done an issue of Batman being inked by Dick Giordano. He called me up one day and said, “Just so you know, when I’m inking your heads, I’m inking the lines just inside the heads.” In other words, if I’d drawn a full figure, he’d ink all the lines from the neck down, but in terms of the head, he’d go just inside my line. It was because I wasn’t drawing figures to heroic proportion, I was drawing them to real-life proportion. Once he said that, I knew I had to adjust.

That, by the way, is the kind of conversation editors don’t seem to have with talent anymore. Dick was managing editor, as well as DC’s best inker, and the ability to discuss things with an editor in terms of craft was a lot more common back then. Sadly, it’s something we as an industry have lost.

KS: If we expand out to the industry model as a whole, what’s something dramatically different now from when you broke in?

DJ: I think the single biggest difference is the transition from telling stories meant for a more general audience to stories meant for a hardcore audience. Back when I started [the early 1980s], we had discussions about sales going up in the summer because kids were out of school, and trying to fashion events that would fit into that time. We were trying to find casual, younger readers and hook them for a few years. We’ve since become a medium much more geared toward hardcore readers, with longer storytelling meant for a collection or trade paperback. That’s not to say it’s all bad — only different.

KS: These days, do you have a set daily (or nightly) work routine, or does it vary wildly?

DJ: It varies based on the deadline structure. In my younger days, I worked crazy ass hours — there was a time I was writing and drawing two books a month [Superman and Justice League]. No one does that anymore that I know of. There came a point where I just couldn’t do it; now, I think in terms of traditional business hours. I do go nights and weekends when necessary, but I try to keep things a lot more balanced. For my own sanity.

KS: You’ve been involved in so many high-profile books and major comic events in your career. Can you cite a particular moment of professional pride from over the years?

DJ: I’m very lucky because I have so many. Getting a monthly book right out of the gate; for most people, that’s something they have to work their way up to. Getting to do Booster Gold as writer and artist. To have an affiliation with Superman like I have for so many years. Even beyond that, there was a time I was writing both Superman and Spider-Man — I don’t think anyone had ever done that simultaneously. Being able to touch so many characters and hopefully leaving those characters in a better place than you found them. Ultimately, what it comes down to is being able to look back at a career and take pride that you were even able to have that career.

KS: We’ll switch to “lightning round” now in order to get some quick hit thoughts from you. First, do Writer Dan and Artist Dan have different preferences in regards to listening to music while working?

DJ: If I’m writing, the music can’t be intrusive. I tend to go with something much more laid back; I’ll even sometimes go with environmental sound stuff. For drawing, it’s gonna get into the harder stuff and some of the metal stuff just because you need the energy a bit more.

KS: Who’s an artist whose work you appreciate now from your pro perspective that maybe you didn’t so much as a reader?

DJ: Frank Robbins. Mike Sekowsky. I just had trouble relating to them back then, but now I look back and wonder why I didn’t see it. It just didn’t feel right, for whatever reason. At least I can look back and blame it on being a moronic kid.

KS: Would you rather illustrate a script by a great writer, or write a script for a great artist?

DJ: That’s a tough question! I would say — in one of those 51-49% type of equations — that I’d rather write the great script. It’s tremendous fun to write something you’re really, really happy with and then see someone else’s vision and talent enhance that. I say that because I always know how it would look if I were to draw it, but seeing someone else do so opens my eyes to possibilities I might not have considered.

KS: What’s one word that sums up a trait necessary for being successful in comics?

DJ: Tenacity.

KS: Finally, what’s a comic by someone else that you look at as an example of the craft at its highest form?

DJ: Maus. To think you could tell the story of the Holocaust with mice… If I’d been a publisher and that idea dropped on my desk, I would’ve said to anyone, “You’re out of your mind.” But it was done and it’s brilliant.