“Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang”

7.15 (aired February 24, 1999)

“Robbing casinos isn’t part of any Starfleet job description I’ve ever read.”

— Chief Miles O’Brien

We love our fictional characters as much as we love our families. In some cases even more so, as, unlike your Great Aunt Mildred, Luke Skywalker never ruined Thanksgiving dinner with any racist tirades. The human mind has an astounding capacity for empathy to the point that we care about the private lives of people, robots, monsters, aliens, and even desk lamps (Thanks, Pixar.) who will never and can never exist. And at the apex, are the crews of the various Star Trek incarnations. There are fans who would happily help Pavel Chekov move or watch Data’s cat for a weekend. With that level of affection, is it any wonder the crew would be just as protective of their fictional characters?

It’s a stretch to call Vic Fontaine fictional, of course. By the comforting, humanistic philosophies of the Star Trek universe, Vic is a living being. He is self-aware, he has emotions, and as far as I’m concerned, gets extra points for his silky rendition of “Come Fly with Me.” And yes, this does mean that if Skynet ever learns its way around the old Sinatra standards, I’m on its side. The point is, despite Vic being entirely created by Dr. Bashir’s pal, Felix, all of his friends regard the hologram as a sentient being. As a friend, really.

He is, however, the closest the writers can get to the idea of a fictional character for their fictional characters while still retaining an element of stakes. The audience cares about Vic. Well, most of the audience does. He was a divisive character when the series aired, and though I love him, that’s not the universal take. So, danger to Vic is danger the audience will recognize as legitimate. He also allows the audience, an audience who is largely responsible for the creation of fanfic in its modern incarnation, their fondest fantasy: to step in and help out one of their favorite fictional characters.

Vic’s program is humming along just fine when suddenly it’s overrun by a seedier element, including one of those showgirl routines which is pop culture shorthand for “the wrong element has taken over this formerly wholesome place.” The wrong element is personified with mob capo Frankie Eyes and his wall-of-beef henchmen Tony Cicci (played by veteran character actor Mike Starr). Frankie is an old rival of Vic’s from the neighborhood, who has settled the imaginary feud he and Vic had by taking the casino over and kicking Vic out on his ass. When O’Brien tries to shut the holosuite down and erase the mobster characters, the program locks him out.

This is a “jack-in-the-box,” basically a plot twist in the long-running games that are holosuite programs. Sort of like finding out the guy who’s been sending you on missions is actually a villain, which you might remember from every game ever. Essentially, this is intended to keep the program interesting, which everyone agrees the program didn’t need in the first place (though you know they will reminisce about it fondly later). They can’t delete Frankie Eyes, so their only options are resetting the program, which will wipe Vic’s memory (He nixes that immediately, and true to form they never once question Vic’s wishes.) or finding a way to deal with the mobster in the reality of 1962 Las Vegas. Vic might have run out of luck, but he’s got more than enough friends eager to help. There’s Bashir and O’Brien, his original fans, Dax, who grew close to him in their shared treatment of Nog, Kira and Odo, who owe some of their present bliss to him, Nog, who owes some of his present sanity to him, and lastly, Kasidy Yates. We’ve never seen her connection to Vic, but she’s arguably the most important from a thematic standpoint.

Two of the crew have no interest in helping. Worf sees Vic as nothing more than a hologram. A pleasant singer, but a mere computer program. Sisko’s resentment of his senior staff’s preoccupation is far pricklier. This is why Kasidy needed to be one of Vic’s fans; she’s the only one who can speak to Sisko as an equal, and as we learn, the only one who could really understand what’s eating the captain. In a scene written by African American literature professor Isiah Lavender III, Sisko and Kasidy have a heated discussion over the purpose behind Vic’s lounge. Sisko objects to the program as, he correctly states, it’s a whitewashed version of history. In the real 1962 Las Vegas, black people were not welcome as casino customers, and it does a disservice to his ancestors to pretend they were. Kasidy counters that the program isn’t meant to be accurate; it’s a depiction of what could have been. What should have been. They can enjoy it without forgetting where they came from.

It’s an important argument to have, and I’m glad they had it. That kind of discrimination is not something that white people have to deal with, and it too easily can be forgotten. Both of these characters, who we love and respect, are entirely correct. These are words that feel at home in their mouths. They are authentic. It’s a way to educate, relatively unobtrusively, in a scene that also serves to define and explore character. Kasidy convinces Sisko, and he joins the team.

The plan is exactly what you’d hope it to be. The crew is going to rob the casino, so that when the boss shows up for his money, he has none. Mobsters have never been known to take financial losses with equanimity, so that should lead to the prompt removal of Frankie Eyes and a return to the good times.

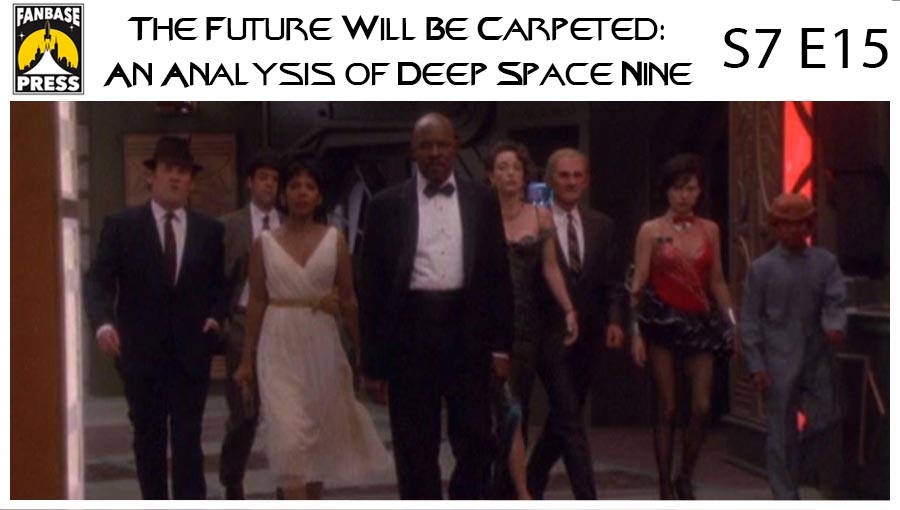

And yes, for those of you counting at home, there are nine people in the team. That means that in this homage to the original Ocean’s Eleven (The Soderbergh remake was still two years off.), we have a literal Deep Space’s Nine. I kind of wish they’d called the episode that.

The plan is the dizzying array of cons and misdirection that you want from something like this. While the heist is certainly simpler than the Swiss watch of that Soderbergh remake, it’s a lot of fun to watch the crew getting into their various roles. Turns out Felix was right; this looks like a blast. The crew comes together, gets past a few of the unexpected hiccups along the way, and pulls off the caper. Just like that, Vic gets his lounge back, and the crew has their favorite haunt.

The episode ends with a duet between Avery Brooks and Jimmy Darren doing a soaring rendition of “The Best Is Yet to Come.” Not only is it a sign that Sisko has made peace with this gentle fantasy of the past, but that he’s come to like the man at the center. And how could you not? This number also doubles as a promise to the viewers. We’re about to enter the home stretch of the series, and in fact this was the last episode produced, though not aired, before the ten-part finale kicked off. DS9 is going to go out on its own terms, and with this musical number, the show is calling its shot. I love the confidence, and after seven years, it’s earned it.

Next up: Section 31 is back.