The trading cards were what did it. Almost everything else made sense, but why the cards? Why market stuff for an R-rated movie to kids who are not actually allowed to see it?

Alien was released when I was ten years old. It was a good time to be a fanboy. Star Wars had been out for two years, changing merchandising along the way (I had a lot of the action figures and the accoutrement that go along.) and paving the way for lots of science fiction and horror in the cinema and television. Battlestar Galactica rapidly followed, appearing the year after Star Wars on ABC. Like its culture-changing predecessor, BSG had action figures, trading cards, comic books, tie-in novels, and all sorts of other fanboy and fangirl gear to keep the party going.

Then, Alien. The commercials for the film screamed that this film was right up my alley. Spaceships, aliens, space, monsters, and even a super-cool tagline (“In space, no one can hear you scream.”) I approached my parents about being taken to see it. Good grades in our home resulted in the dispensing of rewards, and I was a bright, intelligent ten-year-old who did very well in school. I assumed they would see taking me to Alien as a just reward for my academic diligence.

What the heck does “R-rated” mean? Why are we not going? Did they not understand that spaceships meant a movie for kids? I mean, were they not the ones who took me to Star Wars two years before? Several times, I might add. What the heck, indeed?

So, no Alien for me. Disappointing, but such is life. They also wouldn’t take me to the re-release of The Omen. (In hindsight, they were probably pretty good parents). I would see both films when a new technology entered our home about four years later called a Video Home System (or VHS), represented by a Video Cassette Recorder (VCR) in our family room which allowed us to see films as they were, not edited for television. Worth the wait.

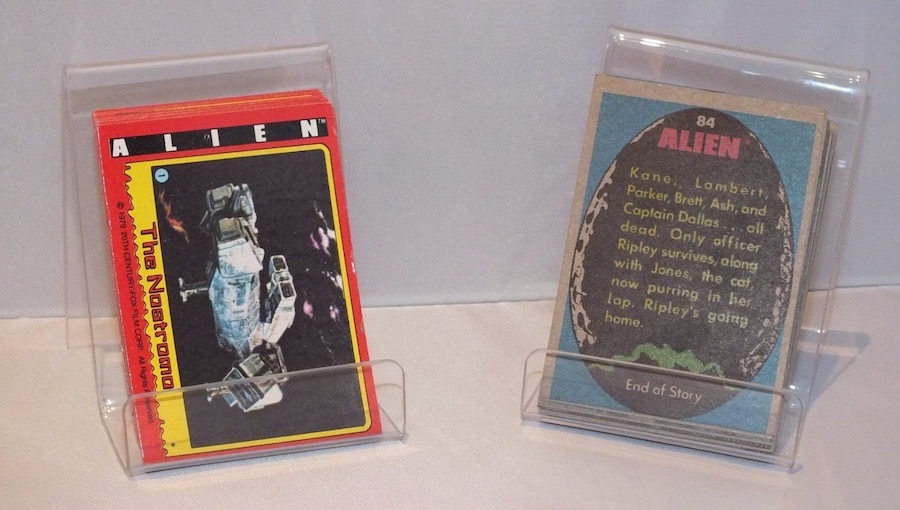

But here’s the weird part. There were Alien trading cards and an Alien comic adaptation (We wouldn’t start calling them graphic novels until the mid-eighties, even though the term had been coined back in 1964.) that were sold in the same way the ones from Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica were. What’s even weirder is the same parents who wouldn’t let me see the film let me buy the full-length comic adaptation (swears and violence and all!) and the cards.

I got the comic book home from Caldors (the one-stop shopping place for ten-year-olds in Connecticut, long since gone out of business) and settled down to read the forbidden film in its allowed form. Cool pictures of space ships. An alien bursting out of a guy’s chest. Cool. Ash is an android. Did not see that coming. Awesome. Then, a full-page panel of Ash’s head telling the crew of the Nostromo that they were expendable and that the alien was a perfect killing machine. “You have my sympathy,” Ash-head told the gathered crew and me, the reader. “Shove your fucking sympathy,” says Parker as he pulls the trigger, unleashing the flamethrower’s power on Ash-head. Violence, the worst swear of them all (Matt Gates had just gotten his mouth washed out with soap the previous week, because his mom heard him say it. It rapidly became a legendary epic in our neighborhood.), and the anticipated horrible death of every character.

Okay, so now I knew why it was R-rated. Somebody said the F-word.

I began collecting the cards – a quarter got you a dozen cards, a sticker, and a stick of pink gum that pretty much tasted like it was made from the same material as the cards. I would buy a few packs a week with my allowance, hoping to get as many pictures of the alien as possible. Even at ten, I recognized the power and beauty of Giger’s art. Prohibited to see the film, I would get everything Alien I could – copies of Famous Monsters of Filmland with the alien on the cover, Starlog, the poster book. Ironically, by outlawing the film, my parents had made everything about the film a necessary possession.

One day, I went into Cumberland Farms (a local convenience store) to buy that week’s Alien cards. The adult behind the counter (Adult to my ten-year-old eyes – in hindsight he was probably a high school student.) picked up the gum and said, “This movie is R-rated.”

“I know,” was my canny reply.

“How old are you?” asked the clerk.

“Ten,” I said with all the weight I could muster.

“Then, you can’t buy these cards. It’s an R-rated movie,” he pronounced, sagely.

“The movie is rated R,” I contended. “The cards don’t have a rating.” (Again, I was a smart smart-ass at ten whose pet peeve was grownups who thought I was less intelligent than them because of my age.)

He flipped the pack over and pointed to the fine print on the back.

“Says right here, this pack is R-rated. Under eighteen can’t buy it.”

“That’s the ingredients for the gum. They are legally required to have that there. It’s not a rating.” (Again, smart & smart-assed. I was already doing an end run around the movie and my parents.)

“You know that, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“It’s still an R-rated movie.”

“So?”

“Your parents know you’re buying these?”

“Yeah. Your manager know you won’t sell them to me for some reason?”

Then, he stopped smiling. Gave me a look of pure contempt. But he then rang up the cards.

“Twenty-seven cents, twerp.”

I put down the quarter and two pennies. He picked them up and put them in the drawer. I stood there.

“What? You can take your R-rated cards.”

“I believe you’re supposed to put them in a bag.” Smirk.

He slowly got a bag, threw the card pack in, and threw it on the counter between us. “Get out,” he said quietly.

“Thank you,” I said, the smirk never leaving my face. As I exited, I quietly said under my breath so that only I could hear, “Shove your fucking convenience store.”

I saw Alien a few years later and already knew the film, but what a treat to finally see the moving version. It was, admittedly, more terrifying than the comic book and cards, and in hindsight, I would not have handled it as well at ten, though I would have tried. I waited for the big moment. “You have my sympathies,” said Ash. Ripley tears out the cord that allows him to speak. “C’mon,” says Parker, and Ripley, Parker, and Lambert leave the room… What? The line I most associated with the film wasn’t even in it? Why was this film R-rated then? Oh, yeah. All the violence. Makes sense. Yeah – at ten I would have tried, but my folks were probably right, in hindsight.

But for me, I have always thought of Alien as the moment my transition from fanboy to fanman began. It was a more adult film that I embraced (even if I didn’t see it) and studied and loved. I still have the comic adaptation (not in the best of shape – c’mon I got it when I was ten!) and the cards. I also now have the entire film series on Blu-ray.

I admit, it was fun to be a ten-year-old Alien fan with my comic book and trading cards, but it’s even better to be an adult Alien fan. Shove your fucking R-rating. I’m going to go watch it again now.