“We are on a journey…Life is a trip from here to there.”

– Will Eisner, To the Heart of the Storm (1991)

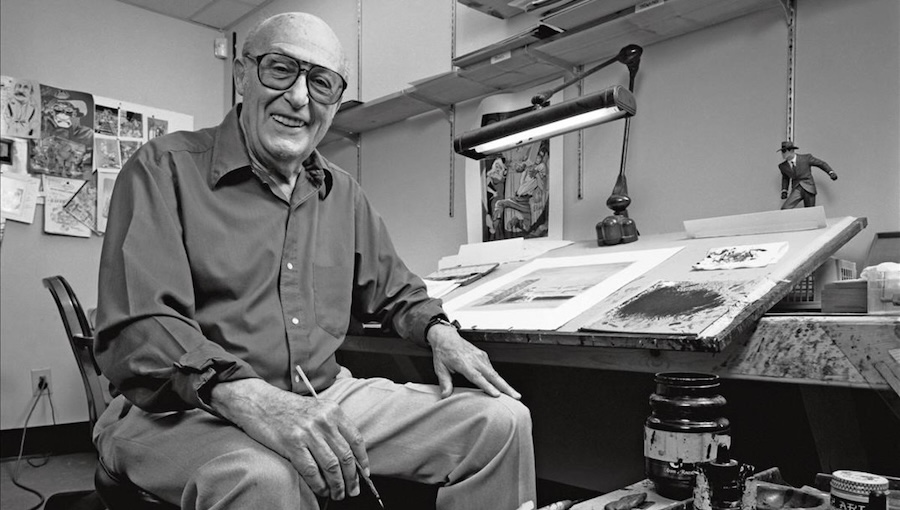

Each year for Will Eisner Week, the life and work of comic book creator Will Eisner is celebrated in comic shops, schools, museums, and libraries to promote sequential art, graphic novel literacy, free speech, and Eisner’s legacy. Eisner was primarily known for his work on The Spirit, his teaching of sequential art, and for pioneering the graphic novel; however, his contributions encompass so much more than that. Eisner’s work from the 1970s to his passing in 2005 dealt with many different themes, including history, the life cycles of generations, memory, raw human emotion, racial relations, and community.

In 2025, personal non-fiction sequential art stories are common, and have been for a while. These range from books with autobiographical content like Blankets by Craig Thompson and Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware to more serious historical accounts like Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman and March written by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell. While creators like Spiegelman had been telling stories of this nature since the underground comix movement of the late 1960s, it was Will Eisner who brought this type of work into the mainstream.

Eisner was inspired and influenced by historical comics and cartoon diaries by creators Justin Green (Binky Brown Meets The Virgin Mary), Jack Jackson (who created historical comics about Texas in the 1800s), and Dan Barr (Kings in Disguise). He had always believed in comics’ literary potential. Eisner was able to have his first work of this type – A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories – published by Baronet Books in 1978 with both a hardcover and trade paperback edition. The book not only told a few memories of Eisner’s childhood growing up in the Bronx, but it expressed the raw emotion of a father losing his daughter and asking the question why – an experience that Eisner himself had.

A Contract with God was only the first creative expression of Eisner’s past. In 1985, his experience as an artist at the beginning of the comic book industry was relayed in the book, The Dreamer, an essential reading for anyone interested in the history of comics or anyone aspiring to become a comic book creator. It shows a “fictionalized” (The names have been changed to protect the innocent, but anyone reading the book with even a fraction of comic book history knows exactly who all of these people are.) account of the birth of comic books. The Dreamer is educational, even including such obscure publications as Tijuana Bibles – explaining what they were and who was publishing them. More importantly, it’s inspirational. It showed Eisner’s belief in himself and his work in spite of the fact that everyone else around him was motivated by money and practicality. One of the hardest things that any artist/creator has to endure is their own feelings vs. reality. It is interesting to note that this book came out just ahead of two works that changed the comic book industry: The Dark Knight by Frank Miller and Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. The Dreamer is the only comic of its type to give an overview of that time period and the people who created these concepts [although a close runner-up is The Artist Behind Superman: The Joe Shuster Story (2018) by Julian Voloj and Thomas Campi].

Reality reporting was another area that Eisner explored. He came out with books like New York: Life in the Big City (1986) and City People Notebook (1989) which were reflections on life in a crowed metropolis and contained short stories that looked like they came straight out of Don Martin’s cartoons in MAD Magazine. These compilations were almost completely silent, emphasizing body language and facial expression to tell the stories. They also employed a lack of consistent panel outlines, allowing more emotion to come through the layouts, as well as the characters.

The New York books seemed to give Eisner something to ponder. He became very aware of inanimate things with a limited life span and began to focus on them. The Building (1987) and Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood (1995) were very different stories with similar themes. Both focused on a specific area and the people who passed through it.

The Building told four stories involving a property in New York – each overlapping with one another. The building in question had been built decades before and was about to be torn down for a slick modern building. The lives of the people who interacted with the building became the fabric of the area, even after the old building had been replaced. The question Eisner posed was about the memory of people and the place that was so important to them.

Dropsie Avenue was about memory, as well. In this case, it was the rise, decline, and rejuvenation of a neighborhood, the people who inhabited it, and the recycling of events. Stretching from the first homes built there in the 1800s, it dealt with historical events, families, community, crime, and racial prejudice. From the Irish, to the Italians, Jewish, Hispanic, African Americans, and current immigrants, it showed how races began as separate entities only to come together for the greater community. It also showed the intolerant who walked away, preferring to be with “their own kind.”

The question of race, especially those of his Jewish roots, played a very large role in the twilight of Will Eisner’s work. His follow-up to The Dreamer was a prequel of sorts called To the Heart of the Storm (1991). Beginning with his journey on a military train to meet an unknown future after being drafted into World War II, the Will Eisner character of the story reflected on his family history. His father was a dreamer artist who left Europe in order to escape being drafted into World War I, and his mother, always worrying and practical, found herself deserted and alone after family tragedy. It is filled with many emotions, as Eisner recounts the prejudice and embarrassment he experienced during his childhood. Despite this, the story is as inspiring as The Dreamer, however, in a more contemplative manner.

As he moved to the 21st century, Eisner became concerned about the prejudice he was seeing: recent antisemitic events ranging from angry graffiti to synagogue bombings and Holocaust Museum fires combined with the knowledge of propaganda being spread bothered him. Will Eisner’s final work was The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This book was pure history: an investigation into forged and fake papers claiming a Jewish plot to take over the world. The Protocols have been used by many, including Adolph Hitler, as an excuse to wage war or try to eradicate the Jewish population. Eisner did not live long enough to see the final product printed.

Eisner’s legacy is far more than a few instructional books. His work transcends a particular time period. It is tales of the people and their environment – families, communities, foreign places, war, love, and hate. It is not enough to “celebrate” the man. It is far more important to read his work, contemplate its meaning, and understand how it relates to our lives. That is the real legacy of Will Eisner.