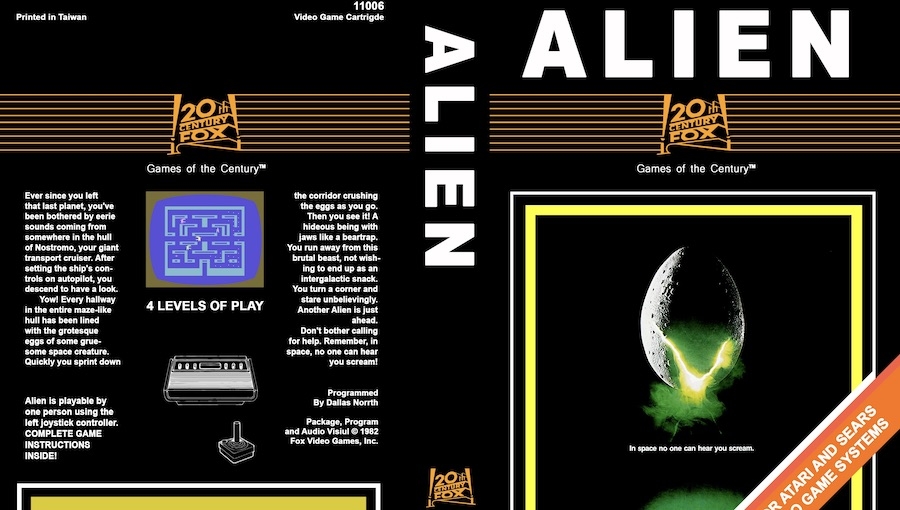

While the movie Alien was released in 1979, the first video game adaptation of the science-fiction horror experience came three years later with Alien for the Atari 2600 home console in 1982. Developed and published by Fox Video Games, a subsidiary to 20th Century Fox, the game can be described in generous terms as being within the “Maze Chase” genre, or in more accurate terms as a “Pac-Man clone.” Alien does not feature power-pellets or ghosts, but it does feature a Flame Thrower. I sense your tracking device is pinging with questions, so it might be best if you read the narrative set-up from the back-of-the-box first:

Ever since you left that last planet, you’ve been bothered by eerie sounds coming from somewhere in the hull of Nostromo, your giant transport cruiser. After setting the ship’s controls on autopilot, you descend to have a look.

Yow! Every hallway in the entire maze-like hull has been lined with the grotesque eggs of some gruesome space creature. Quickly, you sprint down the corridor crushing the eggs as you go. Then, you see it! A hideous being with jaws like a beartrap. You run away from this brutal beast, not wishing to end up as an intergalactic snack. You turn a corner and stare unbelievingly. Another alien is just ahead.

I can’t read “Yow!” without it sounding like Cat from Red Dwarf, with him pivoting and James-Brown juking out of danger, but in Alien we are not informed who “you” is. It could be Ripley, in a dozen pixels or so, with none left for her pre-scalped head; it could be anyone on commission from the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, given that the plot does not match with the unfolding of events from the movie, where there was only the one sizable monster to deal with. In Pac-Man, there are four variously coloured ghosts that stalk the titular figure; with Alien, there are three xenomorphs, each one cotton-candy-coloured like Care Bears. The box narrative also mentions “beartrap” jaws, which isn’t a definition one might use for the monsters in the movie (they don’t unnervingly unhinge, like say, Pac-Man’s do), but within the video game they appear to be lumbering masticators with a nubbin tail and stocky legs for counterbalance; although, if I was going to have a Dali-esque nightmare about a xenomorph, I suppose it would be all about those nesting-doll gnashers.

In Alien, smashing eggs is an interesting motivation for the removal of “dots” from the game arena. This is before the Alien Queen was introduced and her mucous-lubed birthing canon/cannon was established in later lore. Also, it’s quite something to imagine the eggs before they reach a point of maturation in this variation of the incubation cycle, because why you would run down a corridor stomping seven bells out of primeval pumpkins more threatening than Humpty Dumpty’s sweaty cousin I don’t know. Pac-Man’s “power pellets,” enabling him to munch on the pursuant ghosts, are now “pulsars,” turning the player character into presumably some kind of solar-powered rage-robot, all atomic fists and nuclear kicks, at least for a couple of seconds before the natural order is restored. Plot-twist: Maybe the protagonist is Ash, and this is a futuristic holo-simulacrum of one of his shady reports. Maybe I expect too much, and the instruction manual calls your lives “humans” anyway. You can pick up a Flame Thrower to repel attackers, but in a twist of game-design genius, they are aren’t a guarantee of repulsion, echoing the limited threat that fire had in the first film (when compared to its abundant use in later movies). There is also a “hyperwarp passage,” facilitating movement from one extreme of the liminal space to another with a neat dematerialisation trick found within the genre but not within the established universe. As this is a beat-the-high-score type game with no ending, you are also awarded points for picking up “prizes” such as an iconic representation of Saturn, which is far less easy to explain away; it could be a Wey-Yu loyalty card scheme we don’t know about.

While the body of the game is in the style of Pac-Man (1980), there is a bonus round similar to the classic arcade game Frogger (1981). In Frogger, a frog must simply hop from the bottom of the screen to the top. In doing this, the player must move to avoid oncoming traffic on the highway and falling into log strewn watercourses. In Alien, the hoppity frog is a (presumably) shrieking and flailing human that must move in a similar scenario, except the cars are all aliens, the water is all aliens, and the floor is an inky abyss of pitch-black nothing. This task must also be accomplished in eight seconds or less, and the player cannot deviate in any direction other than north, making the constrictions more like the Hail-Mary sprint to the armored personnel carrier in Aliens (1986), rather than any movie scene from which the game is adapted.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, video game adaptations were a new thing that quickly became an oversaturated thing. For the Atari 2600, with every Superman (1979) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1982) that pushed the boundaries of game technology and film adaptation narrative possibilities, there was a reskinned copy of another game such as Alien. There were also poorly made games like E.T. (1982), which has been unfairly maligned for causing the video game crash of 1983, especially when there were other factors involved, such as Atari’s own terrible port of Pac-Man for the Atari (1982), which is somehow a worse Pac-Man game than Alien; however, if one were to consider that the drastic collapse was caused by issues of quality control and the volume of titles being released, attention must again be turned to publishers like Fox Video Games. Although Atari at this point was owned by Warner Bros., like the drinking birds from the Nostromo’s communal table, the profits were there for everybody to wet their beak. In response, Fox Video Games managed to adapt and release Porky’s (1983), a teen sex-comedy turned Frogger-clone, and M*A*S*H (1983), an anti-war war movie turned Operation board game, and made many more games in addition.

Working under the pseudonym Dallas North, Doug Neubauer created M*A*S*H and Alien in their entirety; prior to this, he also designed Star Raiders (1979), considered by The New York Times and The Library of Congress, among others, to be one of the most significant video games ever made. For as much fun as this article has had at its expense, Alien is not a terrible game. It’s certainly more fun for five minutes than Aliens: Colonial Marines (2013). In their overview of the game, YouTube channel Friday Night Arcade points out that the television commercial for Alien does not feature any footage of the actual game. Yet, this is not an indictment on the quality of the game; as will come to happen with the Alien franchise as a whole, the marketable image of the universe is a wider hook for all manner of products loosely connected to the core film products. Ironically, the Atari game is a better adaptation of Aliens, which would not be released for another four years. Production on Aliens only began in 1983 after the lawsuit for profits over the first movie were settled, so while the release of the Alien game in 1982 may appear especially random, one might see it as an attempt to keep the gestating material in front of audiences who were clamouring for more.

We’re spoilt for choice when it comes to Alien video game tie-ins now, but playing Alien for the Atari is like visiting LV-426 for the first time: Sure, you don’t want to hang around too long and the atmosphere is a little inhospitable, but at least you can explore the place where it all started, face-hugger free.

Carl Wilson, Fanbase Press Guest Contributor

Twitter: @CDWilson