Let’s Check in: A Comic Creator’s Guide to Surviving 2024 – Panel Discussion

As conventions return to in-person events, we at Fanbase Press feel that it is important and necessary to provide virtual access to those individuals who

As conventions return to in-person events, we at Fanbase Press feel that it is important and necessary to provide virtual access to those individuals who

Fanbase Press is excited to share the below news from Hammer Canyon Productions, as they announce the upcoming release of their original audio drama, Hobo

UK-based publisher Markosia Enterprises will release the collected edition of Immortalis on Tuesday, January 30, 2024, and the publisher has been very generous to the

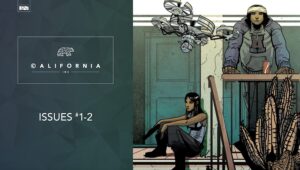

The creative team of the comic book series, ©alifornia, Inc., recently released their second issue, and the team has been very generous to the Fanbase

As the end of 2023 draws near, the Fanbase Press staff and contributors wanted to take a look back at the year’s media from our

Dark Horse Comics will release the second issue of Time Traveler Tales on Wednesday, January 3, 2024, and the publisher has been very generous to

Dark Horse Comics will release the third issue of Usagi Yojimbo: Ice and Snow on Wednesday, December 6, 2023, and the publisher has been very

With Thanksgiving fast approaching, we often find ourselves becoming more introspective, reflecting on the people and things for which we are thankful. As we at

Dark Horse Comics will release the second issue of Masters of the Universe: Forge of Destiny on Wednesday, October 4, 2023, and the publisher has

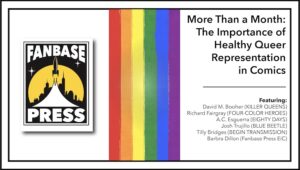

As conventions return to in-person events, we at Fanbase Press feel that it is important and necessary to provide virtual access to those individuals who

Dark Horse Comics will release the next issue of The Lonesome Hunters: The Wolf Child on Wednesday, August 16, 2023, and the publisher has been

In light of the upcoming Eisner Awards for 2023, Fanbase Press Editor-in-Chief Barbra Dillon interviews various members of the comic book community about why the