Warning: Spoilers for the TV series, Fringe, are inevitable. Proceed with caution.

There has been no time in history when humans have not been trying to work out family issues through some form of artistic expression, culminating in an immense catalog of art forms devoted in one way or another to this topic. A quick mental scan through pop culture media will generate an extensive checklist of characters with complicated paternal relationships, including Thor, Tony Stark, Peter Quill, Franklin Richards, Damian Wayne, Tyrion Lannister, Luke Skywalker, Indiana Jones, Marty McFly, Danny Torrance, Wilson Fisk, Michael Bluth, the Winchester brothers, Boromir and Farimir, Carl Grimes, Sherlock (in the Elementary version), Nemo (the Pixar clownfish, not the Jules Verne Captain), and on, and on. We’ve begun a tally that can almost not be completed, and we haven’t even started on the villains with “daddy issues.”

Represented throughout this list are men who have failed in one way or another at fatherhood. Whether driven by good intentions or evil, whether present in the lives of their children or absent, whether seeking redemption or not, they leave an indelible mark on their offspring. The resulting tales of conflict, estrangement, reconciliation, and retribution are some of the most engaging stories you can find in all of fiction.

At the top of this list is the story of Walter and Peter Bishop from the TV series, Fringe. Over the course of five seasons (100 episodes), the show explores every possible aspect of a father and son relationship and tests the strength of their bond in some of the most extreme ways imaginable.

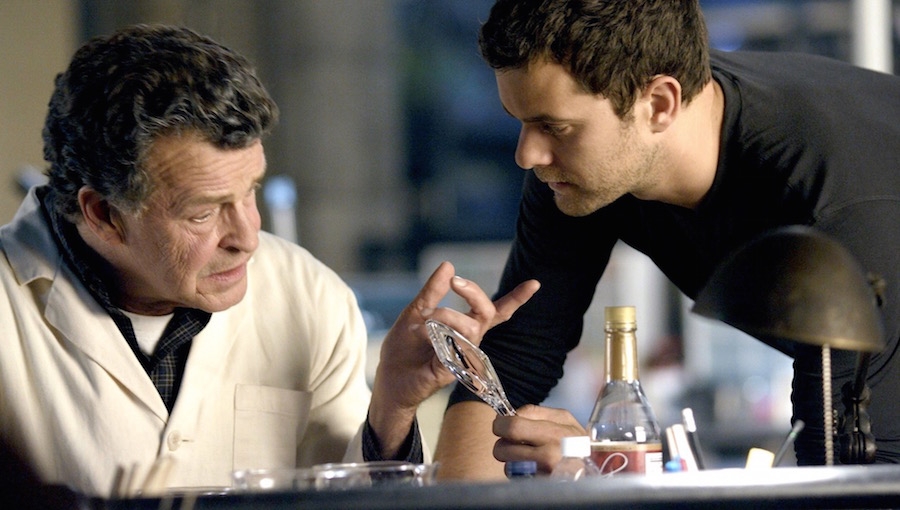

Of course, you can’t have an interesting dysfunctional relationship without at least two engrossing characters. A mad scientist with an unpredictable god complex who likes to self-medicate with milkshakes and homemade illicit drugs? A cynically independent and brilliant jack-of-all-trades who manages to hold down a teaching position at MIT based on a falsified Ph.D.? Walter and Peter definitely fit the interesting bill.

The Walter we meet at the beginning of the series is an inmate in a mental institution, emotionally unstable and, in many ways, unable to care for himself. He is launched back into a relationship with his estranged son, Peter, when he is released into his custody. Peter, very unwillingly at first, takes on a care-giving role for a father for whom he has little connection or respect, frequently having to act as a check to Walter’s extreme behaviors, reminding him of boundaries in morality, ethics, and tact. It’s a rocky start, to say the least.

The Fringe story construct itself plays an immensely important role in the progression of their relationship. Through the use of parallel universes, alternate timelines, and frequent drug-induced forays into subconscious states, it allows for the exploration of extreme aspects of each character and of their relationship. Walter’s doppelgänger in an alternate universe (“Walternate”) is a severe and nearly emotionless man who occupies a position of power in the government and exhibits none of the emotional vulnerabilities and moral regret we see in Walter. When Peter is erased from existence and then re-introduced to the people he loves, and who no longer remember him, we see Peter’s ultimate conversion to a being who needs relationships, including one with his father.

The ultimate question is whether Walter will redeem himself as a father. In order to do so, he has to repair the damage caused, ripping apart space-time to save a young Peter. Such a feat requires an equally severe act of self-sacrifice and the very existence of the universe is at risk. Not many fathers would literally risk the whole universe for their son (or should). With such high stakes at play, this father and son saga earns a spot in the Paternal Issues Hall of Fame.