Last year, Warner Bros. released 42, a sturdy and workman-like biopic of baseball great Jackie Robinson. It’s a perfectly fine movie, handsomely crafted, but also kind of hollow. At the time I saw it, I thought it would be a great movie for middle school Social Studies classes. My 13-year-old nephew saw it at school and loved it. It covers the segregation prior to the Civil Rights era, but it does it in really broad and simplistic strokes. The film never really gives us any insight into the man Jackie Robinson was or what made him tick. He’s just presented as a stoic hero. He’s a bronze statue in his own movie.

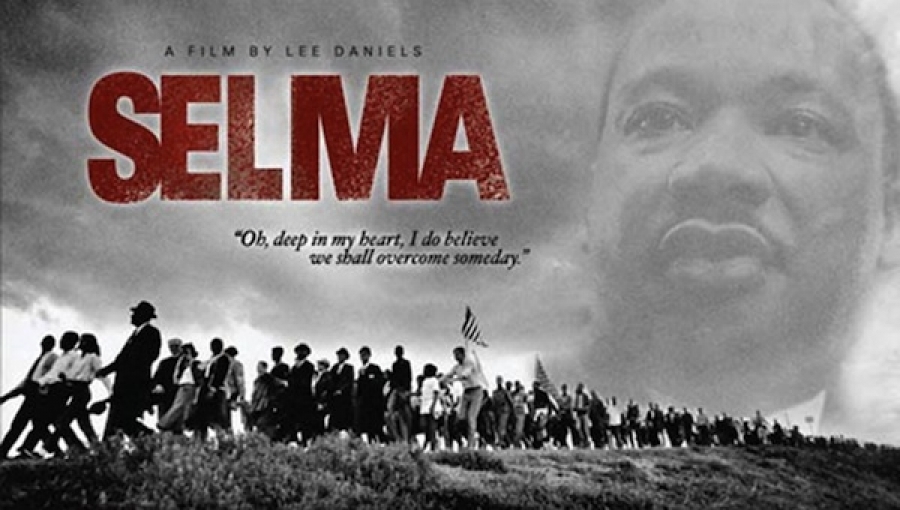

If 42 was for the kids, Ava DuVernay’s terrific, new Civil Rights drama, Selma, is for the grown-ups. Written by Tony Award-winning playwright Paul Webb (He wrote last year’s Best Play winner, All the Way, which starred Bryan Cranston as Lyndon Johnson.), Selma is meticulously researched and, thankfully, focused on a very specific time during the 1960s. Selma examines the time following the Civil Rights Act in 1964, when Jim Crow laws in the South were still preventing African Americans from exercising their rights to vote. Fresh off winning the Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo) is pressuring LBJ (played here by Tom Wilkinson with a slightly wavering Texas accent) into doing more. Dr. King realized that the progress of the Civil Rights Act was mere window dressing if real change was being subverted by denying blacks the vote. Johnson balks at further legislation, so King plans a freedom march from Selma to Montgomery.

The film starts off with three striking scenes: Dr. King winning the Nobel followed by the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham that killed four little girls followed by an elderly black woman (Oprah Winfrey) in the Selma courthouse being denied voter registration, because she couldn’t answer questions on a silly test designed to deny her access. These are scenes that get the blood up almost immediately, and the film becomes more powerful as it garners momentum.

I think it’s an immensely wise choice to have limited the scope of the film to just this three-month span of time. It allows the script to really focus on how the movement was organized, and it allows for more character development; we get to see how the engine worked and it’s fascinating. There were different factions in the movement that didn’t always see eye to eye with the method of nonviolent resistance Dr. King favored. Dr. King had the savvy to know he needed to present dramatic images in the news media to move people from sympathizing with the cause to taking real action. When the first attempt to cross the Selma bridge erupts in unspeakable violence, those images are seen by 70 million people which motivates others (especially the clergy) to join the fight in Selma.

Though I’d never call Selma a biopic about Dr. King per se, he is still the central presence in it. You’re probably familiar with David Oyelowo’s face (He was the villain in Rise of the Planet of the Apes.), but I think they were wise to go with a lesser-known actor to play such an iconic figure. Also, he crushes it. I can’t imagine anything much more daunting to an actor than playing a real-life figure as seminal as Dr. King, both as a historical figure and as a person whose oratory and rhetorical style is so well known. One of the film’s unmitigated triumphs is, unlike the Jackie Robinson of 42, the Dr. King of Selma is rendered as a fully formed, three-dimensional character, largely thanks to Oyelowo’s layered work and a script that doesn’t pull its punches or coddle any sacred cows. Thanks to some underhanded work by J. Edgar Hoover, it’s a matter of historical record that Dr. King was not always the most faithful husband. Thankfully, Selma takes matters like that head on and is a better film for it. Hoover tries to go after King through his wife by sending her a recording of one of her husband’s dalliances in a bugged hotel room. When he tries to deny that the heavy breathing is in fact him, his wife shoots back, “I know what you sound like.” Carmen Ejogo doesn’t get a huge amount of screen time as Coretta Scott King, but she’s great in the time she has, bringing a weariness to a woman who knows the importance of the movement but also knowing what her family is sacrificing in exchange for it. This is a woman regularly taking phone calls with threats to murder her children. Watching the Kings fight for the soul of their marriage is something most films would want to avoid if they were only about mere hero worship, but taking it on is what makes Selma so special. These were real people with genuine flaws doing extraordinary work.

Another nifty aspect of the script is how characters are introduced but their identities as important historical figures aren’t at first revealed. For instance, Dr. King makes a lot of nighttime phone calls to a woman who sings to him when he needs to hear “the Lord’s voice.” We find out later it was Mahalia Jackson. The most effective for me was realizing that one of the young men organizing the protests in Selma (played by Stephan James) was John Lewis, the legendary Civil Rights leader and longtime Congressman from Georgia. The huge cast is loaded with great performances, with a lot of recognizable faces showing up in small roles.

At one point, Bourne director Paul Greengrass was attached to this script, and I’m kind of glad he eventually dropped out. I’m not sure that shaky cam cinema verite thing he does would be the best match with this material. This is only the second film for DuVernay, but this is an extremely confident piece of work. Period detail is spot-on, and it’s been elegantly shot by Bradford Young.

There’s no way to discuss the impact Selma has without bringing up current events. Seeing 1960s protesters in the film being beaten by police in clouds of teargas is exactly what we’ve seen this year in Ferguson, Missouri. A scene where protesters outside the Selma courthouse take on a pose of surrender is chilling in light of the recent “hands up, don’t shoot” history. Today, people are marching in the streets to protest police brutality against young African American men in major cities across the country. Yes, we’ve elected a biracial man as President of the United States, but we still (Still!) have so far to go. Fifty years have passed since Selma, but we’re still fighting the same battles. The Supreme Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act, and now voter ID laws are being introduced in many states as a means to disenfranchise poor people and minorities from voting. Many of these laws have been struck down as unconstitutional. Early voting time is being restricted. In recent days, the Michigan state legislature passed a law making it legal for doctors and EMTs (among others) to deny emergency medical services to LGBT people if treating them violated “deeply held religious beliefs.” Just curious, but whose religion teaches it’s okay to potentially watch somebody die when you have the ability to intervene? There always seems to be some stiff pushback against progress.

There’s no way the makers of Selma could have known about the social environment their film would be released into, but it’s arrived at a very critical hour. This is indeed an important film, but, thankfully, it’s also a very good one. It opens in New York and Los Angeles on Christmas Day and goes into wide release on January 9.

Selma is one of the very best films of the year.