“Between the Panels” is a bi-weekly interview series focusing on comic book creators of all experience levels, seeking to examine not just what each individual creates, but how they go about creating it.

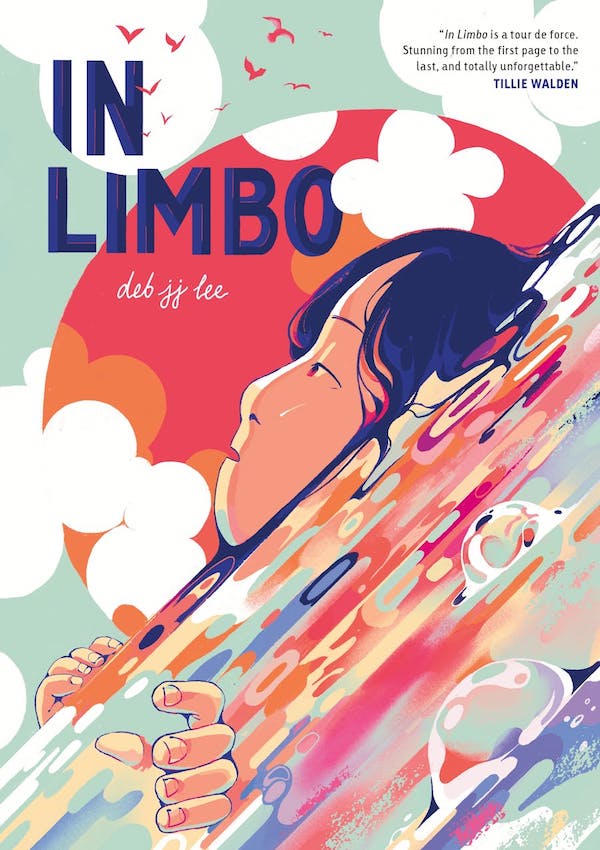

Remove “comics” as a category from Deb Lee’s resume, and one would still be left with an impressively wide-ranging display of artistic accomplishments. Fortunately, the comics world also gets to benefit from Deb’s talents — their newest project is the Ignatz and Harvey Award-nominated autobiographical graphic novel, In Limbo (available now).

First off, the basics…

Your specialties (artist/writer/letterer/inker/etc.): Artist, Writer

Your home base: Brooklyn, NY

Website: debleeart.com

Social Media

Instagram: @jdebbiel

Twitter: @jdebbiel

Bluesky: @jdebbiel.bsky.social

Tiktok: @jdebbiel

Tumblr: @jdebbiel

Fanbase Press Contributor Kevin Sharp: As a creator and storyteller, what does the comics medium offer you that maybe others don’t?

Deb JJ Lee: I tripped into publishing by initially making the comic that would become In Limbo, which was about trans-generational language barriers. That must have been my first or second comic ever, and it was the best way to describe all the angst I was feeling about living in a very Korean area for the first time without my parents. And it was either that or write a long essay (I’m very self conscious about my writing.) or draw one illustration (which wasn’t enough). The amount of time it takes to make a comic is enough to let me healthily process this transitional part of my life.

KS: Can you recall your earliest exposure to comics growing up? I read you say that you weren’t allowed to read them… looking back, do you think that “forbidden fruit” element made them more appealing?

DL: It must have been Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes. My third grade classroom had a bunch of Chicken Soup for the Soul books, which had a bunch of strips from the comic. Even though I wasn’t allowed to borrow or buy comic books, my mom did relent to getting us the collection to occupy my and my brother’s time on a flight to Korea. But those were hidden in the closet before the trip. Especially after getting a smartphone, the “forbidden fruit” aspect didn’t make comics as appealing as it did for me trying to read them as fast as possible. Just to race through them while I was at the bookstore or library.

KS: Was there a particular comic book story you read that really struck a chord with you?

DL: I think it was Oyasumi Punpun (Goodnight Punpun), when I was 18. When I finished it, I couldn’t sleep that night.

KS: What was it about that that got under your skin?

DL: Maybe it was because I was freshly graduated from high school and it was a time to reflect on the last 18 years of my life, but also I was still raw from my second suicide attempt—the one that happened in the book—so I was extremely susceptible to depression.

KS: What kinds of opportunities did you have to practice your art, either on your own or in a more structured environment?

DL: The first drawing I remember was a red elephant on the wall in colored pencil. I think I was four, but I didn’t take my first art class until I was seven or eight. I took occasional classes at the local art center but wasn’t as serious about art as a general practice until 14, where my improvement really began. This was when I got Tumblr and a DeviantArt account. Because I knew exactly which colleges I wanted to go to by freshman year, I applied to only four schools. And it wasn’t until 21, my last year of undergrad at Carnegie Mellon, when I decided to pursue illustration as a serious career.

KS: Had the idea of an artistic career arrived for you before then?

DL: During my UX internship at LinkedIn, I used my first paycheck to purchase an iPad and Apple Pencil and haven’t stopped drawing since. By August, I realized that illustration was the only thing that truly made me happy and in September I realized that people could actually freelance in this field! However, I was truly lucky because LinkedIn gave me a return offer, which meant I didn’t need to spend senior year looking for a job. I scrapped the UX design portfolio and started over with a blank illustration website, which I have been adding to ever since. I was truly obsessive at the time—Pinterest illustrations were the first thing I would scroll through in the morning, and last thing I would see before I went to bed.

KS: During college, what did you envision—either specifically or generally—as the path that ultimately led you to LinkedIn? Was that UX job something more to pay the bills or was it a potential springboard to something else you were more passionate about?

DL: My program was in Design, specifically communication design/graphic design. And because [Carnegie Mellon] was largely focused around engineering and computer science, we had close ties to Silicon Valley; therefore, most kids in my college went to work for Google, Apple, Facebook, back when that was a cool and noble thing to do. It was the default path for us. I didn’t touch illustration as a career idea until after my LinkedIn internship before my senior year—a struggle because my university as a whole did not support this path. We maybe had five books about it in the main library. I would even go so far as to add that I was actually discouraged by a few professors from pursuing it. I heard about one of them even saying that “illustration is the lowest form of art.”

KS: Please talk a bit about that time around building your site. What goals did you set for yourself as far as producing work, and what steps did you take to get it in front of people?

DL: I have to credit my design background for this. Tech recruiters have so many applications while having so little time, so the less clicking they would have to do, the better. I believe it’s the same for art directors, though there is less information required to show that one is capable of taking an illustration gig—whereas a UX design portfolio requires written insight about research, process, prototyping, etc. I spent my fall semester of my senior year in deep imposter syndrome. The RISD, SVA, and MICA kids all spent four years in illustration, while I was just getting started, so I did everything I could do to “catch up.” Every week I would make —with soft prompts and deadlines from a photography professor— a mock illustration to put on my portfolio. Every Monday, my blank website was filled with one more piece, and by spring semester, I was ready for opportunities.

KS: How about making your own comics? Had you played with the form when you were younger at all?

DL: I toyed around with little comics when I was seven to nine years old. But it was essentially stapling computer paper together to make a book, and drawing a story in it. There must have been three or four of them that I proudly displayed on my bedroom windowsill before my younger brother found them and laughed! But that was it, until 2018 I believe.

KS: Can you expand on how you “tripped into” publishing? Making it in any creative field requires some combination of talent, preparation, and right place, right time — how did those factors balance out for you as far as getting your first work published?

DL: Back in my spring semester of senior year, I had a decently-sized portfolio that I could send off to art directors, competitions, etc. Around January was the call-for-submissions for the Society of Illustrators Student Competition, to which I applied—turns out no one from Carnegie Mellon had ever applied, so we had to register our school—and did very well in! The Society’s Twitter account posted my drawing, and that’s how my literary agent found me. At that point I was a tad reluctant because I was leaning more towards the editorial industry, but I decided to give publishing a shot. My entrance into editorial illustration happened around the same week actually. I had applied to the NPR illustration internship, which opens up once in a blue moon, and in spite of all odds, I got the job.

KS: Jumping ahead to your book, In Limbo… When did the idea of this as a project first come to you, and what was the shape of your creative journey from that point to completion? I’ve talked to some creators whose new book was actually a product of years of tinkering, whereas for others the project was their sole focus from when they decided to do it until it was finished.

DL: I think [it] was an idea that came from both long-term and short-term thinking. Since I was 10, I knew I wanted to make some archive of everything that already happened in my life, as at that point I’d already been suicidal and hurt due to racism and family abuse. The urge came back at 18, after the events depicted in In Limbo occurred. But it wasn’t until 2018, when I, a 22-year-old Bay Area transplant, posted a comic about transgenerational language barriers. It was only four pages, a weekend project. But when the post went viral, I realized how common of an experience my story was, and my literary agent suggested I make a graphic novel around it. Quickly, I understood that if I’m making something about language, I’d have to make it about Korean-American identity. And if I’m making a story about Korean-American identity, it would have to stretch into trauma. The language barrier bit ended up becoming a speck of dust.

KS: Because this work is in the memoir space rather than a story you invented from scratch, what was your process for sifting through everything you lived through to decide what would make it into the book? Is it extra challenging to look at one’s own life with objectivity to find “the good parts?”

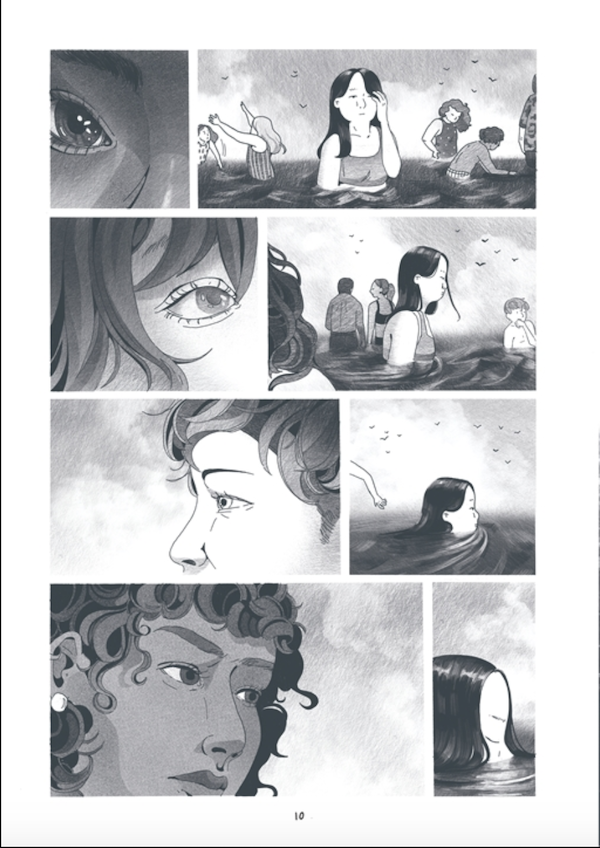

DL: Finding happy moments was much harder than I expected! My life [was] already so dark, and recalling any less-than-pleasurable moments then felt corny and disingenuous at first. And with so many difficult scenes, I had to make sure that the happier ones really mattered. In terms of sifting through memories and material, the story started out as chronological. Every conversation, every interaction, every mental breakdown was stuffed in the first draft that came out to be over 500 pages of word salad of repeated microaggressions. Therefore, we spent the next drafts cutting, combining, and condensing. With that being said, this created dialogue and storylines didn’t happen exactly how they played out a decade ago, but still, I made sure that the reader left those scenes feeling the same way I did. The contents of In Limbo didn’t happen word for word in my universe, but I know they did in some alternate dimension.

KS: For a personal project like that, do you have any trusted beta readers who give you feedback on your work before it’s ready to leave the nest?

DL: Hmm, I had a some close friends read it at the halfway mark. But really, I only let a couple people, including a partner I had at that time, read it every 50 pages or so.

KS: What’s a hobby of yours totally unrelated to art or anything you do professionally? Could be something you study, collect, practice…

DL: I hate to sound like a gym rat—but since I graduated from undergrad, I’ve been working out very regularly! I was also into long-distance running and even completed my first marathon last year, and I did very well, but I’m not doing that again. Burnout has finally hit me, so I’ve been reading again instead of dragging myself to exhaustion on the daily. I’ve missed the times in my life as a kid when I would come home from the library excited to read what I got. I’ve even stopped working on the subway and instead would bring my current book. (Probably safer; iPads are too expensive to carry around everywhere.)

KS: To close out, please let readers know of anything aside from In Limbo that you have coming down the road.

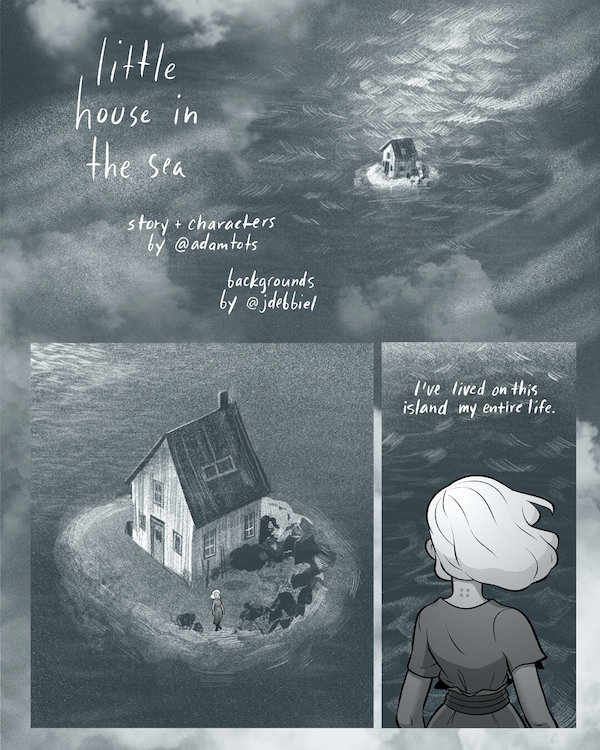

DL: Really, I’m just trying to chill out. I do have my next graphic novel with Harper Alley—written by Tina Cho—publishing next fall. There are also some picture books on the horizon that I should get started on after I take a few months off from books entirely! Other than that, I’m still taking freelance work—but not too much.