“Between the Panels” is a bi-weekly interview series focusing on comic book creators of all experience levels, seeking to examine not just what each individual creates, but how they go about creating it.

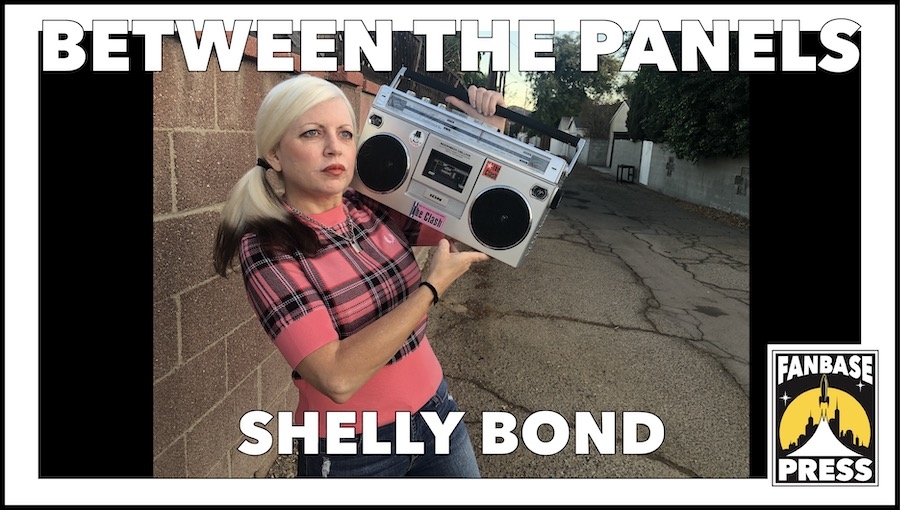

From her start at 1980s publisher Comico (RIP), to getting in on the ground floor at Vertigo (ditto), to starting her own publishing label, Shelly Bond’s professional journey could be held up as a map of modern comics editorial overall. She’s worked hands-on with some of the biggest names in the business and has survived to tell the tale(s).

First off, the basics…

Your specialties (artist/writer/letterer/inker/etc.): Editor

Your home base: Los Angeles, CA

Website: offregister.press

Social Media

Instagram: @sxbondimprimatur

Twitter: @sxbond

Facebook: Shelly Bond

Fanbase Press Contributor Kevin Sharp: The first question I ask to each guest, which is kind of the overarching question behind all of it, is why comics? What is the appeal of this artform for you personally?

Shelly Bond: Comics is the ultimate art form. There is no other media that is so immersive that you can produce within a matter of months and have a tangible object in your hands. I think there’s no greater way to express what’s going on in your head than by collaborating with others who can help you bring a story or a concept to life and share it with the world. Because all we really want to do is connect with each other. Even those of us who consider themselves existentialists and hate people, there’s no greater way to put your dreams, your aspirations, and what is irritating you on the page. Pay it forward to create a better world. And also, where else could I ignite a revolution every couple of years? Only in comics. And when I say comics, I mean indie comics. 100%.

KS: You came to comics as a reader a bit later in life, correct? It wasn’t a childhood love.

SB: My comics 101 story started in college. I didn’t read comics as a kid. I tap danced, I was a baton twirler in high school, and I was not interested in reading because it’s all my sister did. So, I had no interest in words. Honestly, the closest connection I had to comics was having a crush on Marine Boy, which was a Japanese cartoon in the ‘70s. And I loved the Peanuts gang, so I did read the newspaper strips. The other connection I just remembered recently was that my uncle bought my sister and me matching baby chicks, little chickens. We called them Betty and Veronica, but I didn’t read comics and I didn’t read much of anything. No lie. My mom was a teacher, go figure.

KS: How about movies? When did that love start?

SB: I really loved film and TV. I was a part of what I call “generation MTV.” I was the kid who was glued to the set on August 1st, 1981. You know, desperate to be a New Romantic forever. When I discovered comics, I was in a screenwriting class in college — I’m sure Will Dennis has a very similar story. Our teacher was talking to us about storyboarding, which is such a different thing than comics, but it was a terrific idea to use a comic book as a teaching tool. It was eight o’clock in the morning. Will was a transfer student, so he had to take that class. I was a senior, had just come back from a semester in London, did not wanna be there, was grumpy. But I took my classes in college very seriously, so I was there, no problem. The teacher held up Peter Gross’s Empire Lanes. I didn’t even know comic books were still made. This was 1987. So, my mouth just hung open until it hit the floor, and Will must have noticed because he said, “If you like that comic, you have to see what else is coming out right now. There’s a comic book store in the Commons [center of town]. I think you’ll like those comics.” And sure enough, I went into the comic book store and discovered Grendel #16 and 17, which was my gateway drug. Matt Wagner, give him props 100%. Love and Rockets, which is still my favorite comic book. I’m a huge Gilbert Hernandez fan— his work brings me to my knees to this day. Also some other painterly comics by Bill Sienkiewicz. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I thought, “This is fine art. This is not the comic book art that I’m familiar with.” And that was that.

[Author’s Note: For the Will Dennis experience of this same period, you can find our chat here.]

KS: What did your life look like post-college, as far as when working in comics became a consideration?

SB: I graduated with a degree in film, video, and audio production. I sent out 212 resumes. I heard back from a few places that weren’t interested. I had no experience. So, I was a DJ for the summer and moved to Philadelphia on a whim. First day at the comic book shop — Fat Jack’s Comicrypt — I walked in to start my pull-list, which included Hellblazer, Doom Patrol, Love and Rockets, and I was told that there was a position open at Comico, which was ”close by” in Norristown, Pennsylvania. I sent my resume, and was lucky enough that Diana Schutz was willing to give me an interview. I took a train out to Norristown, which was 52 minutes from my apartment in Center City, walked two miles to a dilapidated duplex, and met Diana. She was great. She gave me an editing test, and to this day, she still gives me credit for the highest score, which is shocking for somebody who wasn’t a reader. So, go figure. After that, I never looked back. No regrets. Feel lucky. And all I want to do is pay it forward.

KS: Before Will alerted you to that store and this new world opened up, do you recall what kind of career vision you had for coming out of school with a film degree?

SB: I wanted to make music videos, and film and hair design videos, because one side of my family is in the dry cleaning business. The other side is in the beauty business. I’m not a diva, but I should be because of my family history. My uncle worked with UK-based Toni and Guy in the early ‘80s. They have very famous shampoo and beauty products in pharmacies and hair salons all over the world. When they were starting out, they had a school in London and a few salons, and my uncle brought them to the States to teach a seminar and instruct at beauty conventions. I was lucky enough to help them backstage, and I was certain that’s what I wanted to do with my life — I wanted to help them create hair design videos and also music videos. I must add the funny story about my uncle, who, by the way, is doing quite well for himself, but said his biggest regret was that Toni and Guy asked him to invest in their company. He thought they had talent, but he wasn’t quite sure if they were going to make it. He held onto his money and it’s his greatest regret. I tease him about that all the time. Maybe I would’ve been a partner had that happened. But then we wouldn’t have my comics, so it’s always a tradeoff.

KS: You mentioned the comic series you really gravitated to back then, but was there a particular story that stands out in your mind as one that really had an impact on you as a reader?

SB: Matt Wagner was bringing his love for literature and classics and mystery into Grendel, and it blew my tiny mind. Issue #16 and 17, which featured many tiny panels, was what I thought of as very much “post-punk” storytelling. It was unlike anything I’d seen; it was erratic but it was so beautifully composed. I’m a frustrated graphic designer at heart, so I took a lot of art classes at school, which were heavy on film, sculpture, and 3-D design. I’m always looking for the composition on the page. And Matt had that in spades. He had such a great positive/negative page balance, black, white, and red. It was really Matt’s work on that Grendel storyline. I didn’t care for the Christine Spar early Grendel; the first 12 to 15 issues weren’t really for me, but everything after that, starting with #16, the Eppy Thatcher storyline… Matt’s writing was the future then, and I think is still the future now. To me, he is one of the industry’s finest.

KS: As far as getting in the door at Comico, did you know at the time or can you look back now and speculate why Diana called you for an interview?

SB: Hopefully, my cover letter showed her that I had more interest in finding out about the comic book industry. Interestingly enough, and I’ve been teased about this a lot, my cover letter back in 1988 had a black-and-white photo of me on it, posing in front of a staticky monitor. It wasn’t just like a beauty shot. I did that because I was told, “Do not put your photo on your cover letter or your resume.” It was the number one tip from anyone who was advising you on how to score the big job interview. That’s why I did it. I came up with a slogan: “Picture me working for your company. I have, and here’s why.” And I listed all the reasons. For Diana, I said, “Huge fan of Grendel,” which was her baby, you know— I mean, Matt Wagner was married to her sister at the time. So, a Grendel enthusiast who was college-educated, who liked French New Wave films, who liked goth music… I wasn’t your typical comic book geek. I was a different kind of nerd. Don’t get me wrong, I’m only here because I’m a weirdo like everyone else, but at that time there weren’t a lot of women in comics. First of all, I think she wanted to give me a shot because she’s a woman in comics. You know, why not? Also, I don’t think a lot of people were willing to relocate to Norristown, Pennsylvania, and I was already there. You’ll have to ask Diana the truth, but I’m certain when I walked in with my giant Robert Smith hair and my silver lipstick and Doc Martens, she must have seen me as this arty girl. I looked 11, I’m petite, and I almost wonder if it was part pity, but also part, “Hey, maybe this person is really good.” And I apparently aced the proofreading test, so there was that.

KS: When you showed up for work on your first day, what was your job title? I assume you didn’t start as a full editor, but did they have an editorial department structure?

SB: Rarely does anyone start as an editor. At Comico, I was an editorial assistant, which meant that I answered the phone, I sent out the comps, and I stuffed submission envelopes with rejection letters. Diana set me on my course with an organizational method and structuring my day unlike anyone else. All the basics you need to know when you’re a kid out of art school or film school— like, I didn’t know about a to-do list, I didn’t know about keeping a desk blotter in front of me and writing my deadlines down on a calendar. You have to remember, Comico was in a dilapidated house. It was a duplex. One side was an indie publishing company and the other side was a physical therapy office. So, you have the owners, the Lasorda brothers. Dennis Lasorda was the money guy because he had a business; he was a physical therapist. All day long we would hear the klang klang of bodybuilding machines. On the Comico side, it was a little more run-down and everybody’s office was in the bedroom. So, Diana did the greatest thing for me—she set up a chair at her desk, which was the master bedroom in the front of the house, and she sat me on her left and she spread all of her documents out.

She had the script, the pencils, the inks, the red pens, the dictionary. And I learned by looking over her shoulder. She would explain things to me, point things out to me. It was not patronizing, it was not condescending, it’s how it’s done. And comic book editing is a very difficult skill to teach, which is why I tried to put it on paper in Filth & Grammar: The Comic Book Editor’s Secret Handbook. And it was still tough. The best way to learn how to edit is for somebody to push you off the diving board, and show you how it’s done. Then, you take what you want from your mentors, from people like Diana and Karen [Berger], and you develop your own systems.

KS: Your first comic was E-Man, correct?

SB: Yeah, that’s right.

KS: What was it like working on that? What did you feel like you could contribute, being so new to the business?

SB: I think the best thing you can contribute is your enthusiasm. In February, I finished teaching a month-long course on editing comics and self-publishing, and what I say to the students in the beginning is to set expectations. You need to know what people are expecting from you, whether you’re teaching or whatever you’re doing in life, and also deliver on your promises. Even if you’re a complete novice.

The other great mentor of my life would be Rick Taylor. As much as I appreciate Diana and Karen—and they were amazing—without Rick Taylor, I wouldn’t be here today. When Diana left the company, Rick and I spent a year plastering the walls and putting band-aids on whatever was left of Comico. Phil Lasorda, RIP, offered me the editorial department when I was 22 years old. He said, “I’ll give you a raise of $1,500.” I was making $16,500. I will never forget it because the best way to learn any skill is to just jump in, make mistakes, fess up, and move forward. So, I had a really, really strong foundation growing up in a family business. My dad took no prisoners and did not treat my sister and me like princesses. We were working from when we were very young, helping out at the dry cleaning plant. For my sister, that meant answering the phones as the receptionist. For me, it meant putting on my Sony Walkman—with first-generation orange ear pads!—and sorting through hotel dirty laundry and pressing sheets and pants when necessary. Nothing was off limits for me. If Diana asked me for a comp copy of Fish Police #2, and it was in the basement that was flooded, teeming with rats and silverfish, I went downstairs in my galoshes and I got those comps.

KS: Talk a little more about Rick, as far as the practical job skills he helped you with.

SB: Coming to the job with no expectations and no fears— two very important traits— I was lucky that the people I worked with didn’t mind a newbie asking questions. That’s where Rick was not only my best mentor, but a very good friend. To this day, I thank him. He taught me color theory. He taught me how to mark up a galley and how to put a letter column together and to burnish a stat on a page. How to wield an X-Acto knife, even before I felt comfortable wielding a red pen.

KS: To take a step back, Comico was one of those companies that came onto the scene in the ‘80s and then was off the scene by the end of the decade. Was all of that happening while you were still there, before the move to DC?

SB: When Bob Schreck, who was the marketing director, and Diana left for Dark Horse, Diana still fulfilled her editing commitments because Grendel was her book. So, I was the managing editor; I was pretty much the contact person for the editorial department. I was editing my own projects, I was working with Steven T. Seagle and Michael Allred on a book that never came out called Jaguar Stories, which was incredible. We even had a line of black-and-white books called Key Line, which was gonna be coming out. The company declared Chapter 11, and then it declared Chapter 7. I was dealing with very tight editorial schedules to get books like E-Man and Empire Lanes to the printer — and The Elementals, which by the way, I chased Bill Willingham around the country for about nine months and got a few issues out of him. The person who took over Comico wasn’t very interested in keeping the current staff on board. He was based in Chicago. I had no intention of moving to a new city, I loved Philadelphia. My partner in crime, Rick, actually submitted his resume to DC very shortly thereafter, and was hired as a production manager.

KS: What was your thought process at the time? You’d gotten into this business and now it was slipping away, at least your first home in comics.

SB: I was kind of at a crossroads. I didn’t really want to leave Philly. I also had this film and video and audio production degree, and I thought I would give that a try. So, I spent two years in Philly working in film and TV, which led me to casting, which led me to become a talent manager for Edie Robb Talent Works, that had offices in Philadelphia, New York, and California. I made some really interesting connections and I actually learned my way around New York City by giving directions to the parents of kids who would audition in NYC for Broadway and Off-Broadway. So, before I even moved to New York, I had a greater understanding of the Lower East Side versus the Bronx versus Harlem. The five boroughs made sense to me.

KS: During that time, did you want to get back into comics at some point, or could you have been happy that had never happened?

SB: Oh, I missed comics a lot. I faced quite a bit of discrimination in film and video. I was hired by a young female filmmaker who was a producer; she hired me based on my resume, and an issue of The Elementals. She looked me in the eye and said, “What you did in comics is extraordinary. I would love to work with you, but you are not going to ever feel the satisfaction of what you did here. I see your name [in the comic]. That is so cool.” I wanted to work with this woman because she was interesting to me, too. She was an indie filmmaker and I wish I’d stayed in touch with her. She was incredible. At the end of the day, I was still reading comics, but I missed getting my hands dirty. Rick tipped me off a few years later when he said, “Hey, Karen Berger is looking for a new assistant editor.” I faxed my resume in. It was that time of technology where I could do that, but then again, I knew a fax in the machine was going to look terrible; it was going to be streaky, not fresh and polished. So, I drew a giant star on the cover letter and I put my own Ben-Day dots on it, so that she wouldn’t miss it when she went to pick it up. [laughter] I hope [what] people can get from that is this: You gotta stand out, you gotta make your mark. Even if you’re shy and unassuming like I am.

KS: You arrived at DC right on the cusp of the official Vertigo launch?

SB: I came to DC in 1992 as a Vertigo assistant editor with skills beyond that mere title, which by the way, Karen explained to me at the time, she only had the position open for an assistant editor. Even though I might have dropped that I was overqualified, this was the job. So, she said that if I proved myself, she would do her best to help me get promoted to associate [editor], but there were no promises. I respected that and I took a pay cut and I changed my life in two weeks because I was hedging my bets that she was telling the truth. I wasn’t a kid when I started at Vertigo, I was 26. Something I want to impart to your readers is that editors’ jobs are not for the fainthearted, and an assistant editor is not an entry level position. You really have to know your stuff if you’re going to survive at a big company at that level. Fortunately for me, Karen gave me a shot. Fortunately for Karen, I came in and I was up and running because she had an entire imprint to oversee. The launch of the imprint was a month after I blew into town on December 12th, 1992. I think we were both really good for each other at that time. I love going on record to say that I think Karen and I as an assistant and editor team were unstoppable, because she put a lot of pieces in motion and I wasn’t afraid to propel them forward.

KS: And you jumped right in on one title fans think of as pure Vertigo, but that had actually been around before the label.

SB: I was starting on The Sandman with issue #46. I was working with Jill Thompson on the art, at the precipice of a new age in color and in digital separation and production. Neil Gaiman told me that when I came on as assistant editor, there was someone who understood color theory, and understood the difference between a color hold and color in the gutter. Neil and I really bonded over what we could do visually to make The Sandman look amazing. I think that’s what happened with “The Kindly Ones.” I think the Marc Hempel storyline with inkers Richard Case and D’Israeli was a real standout, because we were able to communicate to color separators in a way that was unheard of before, and to continue to grow and make the comics look as beautiful as they read in the script and in our heads.

KS: Why do you think you fit in so well at Vertigo?

SB: It was everything I ever wanted out of comics. My love for comics and music are equal, and I really would not be able to choose if I could only have one forever. I was really impressed with Grant Morrison. I mean, I thought he was the living end and I still think Doom Patrol that dovetailed into Vertigo was a masterclass. His trick, at least in my mind, was that every issue of Doom Patrol back in those days was self-contained. Whether it was part three of six, you knew who the characters were and they were a bunch of freaks and weirdos. They were misfits. If he mentioned Dadaism, I was going to the bookstore to find out what that meant. If he was talking about the Ramones, I was getting a Gabba Gabba T-shirt. [laughter] I can’t even express to you what Doom Patrol meant to me at that time.

Peter Milligan’s writing shattered my mind into thousands of pieces that were put back together each and every time I worked with him in those early days. Shade, the Changing Man for me as a young editor taught me everything I needed to know about monthly comics. Just from looking at Chris Bachalo’s artistic development from issue one through issue 50, my hands would shake when those pencils came in. I couldn’t believe my eyes that somebody could create these lines and salute modern art in the way he did. From his covers to his last page of interiors, he is still a trailblazer.

KS: I so clearly remember reading the Shade issue with the JFK assassination [#3], which was insane in the best way. That series almost feels forgotten today, certainly outside of hardcore Vertigo aficionados.

SB: The greatest sin in comics was that Shade was not fully collected. Karen and I went to bat for it many times in our careers, so I still feel bad for Milligan because I think he’s the one overlooked genius in comics. Both Neil and Grant have been given accolades, well deserved. Milligan is the one who I think, if there’s only one left standing, it’s him. He’s the next-level, post-modernist comic book writer, at least on the work that I’ve read and that I worked on with him. The only superhero work of his I read is anything he does with Michael Allred. I put them together on Winter’s Edge, so when they met on Shade, I take all the credit. Mike will acknowledge that; Milligan, not so much. But you gotta love him for that. [laughter]

KS: Diana and Karen are certainly key figures not only in your career but in comics overall. Were they alike at all as bosses?

SB: Night and day. Completely different ends of the spectrum, which makes me sort of monkey in the middle, I guess. Both had very specific, distinctive visions for what kinds of comics they wanted to make, and how they were going to go about making them. As an assistant, you adapt, because you are riding shotgun. I worked with Diana less as a partner-in-crime because Diana ran her own show, so I was absorbing Diana by osmosis — making sure her freelancers were paid, making sure the comps went out, making sure I returned her phone calls, and maybe making some last-minute corrections if she needed them. It was a very different relationship with Karen. It’s a good thing I brought my own jetpack because I was given the responsibility of running her books with her approval. We had a very specific way of working together, but she trusted me a lot, and I’ll never forget that.

KS: If you heard somebody in comics described as a “good editor,” what would that mean to you? Would it be personality, skill set, or some combination?

SB: Let me explain to you what I think a good editor is, and then let me tell you what a great editor is. A good editor is on the ball. They keep the trains running and they can herd the cats. They can make sure that people hit their deadlines, and they make sure that the work that comes in is terrific. They’re enthusiastic and they make sure that the art or the script that comes in gets into the right hands within the company, whether that means the production department, whether that means the proofreader, they make sure that their freelance talent is happy and comfortable working. That’s a good editor.

A great editor makes sure that everybody is not only doing their best work, but they’re having a good time, and that they know they’re part of the collaboration, and they are getting feedback that’s constructive, that’s both immediate, and that can help them hone their craft so that you can all elevate the art form. A great editor is also a great idea person. So, when a mediocre idea comes in, that great editor can help that writer take what’s in their head that maybe has been done to death, and think of a new angle to make it something we haven’t seen. A great editor can see from 50 feet or from one panel where a young artist has particular talent. Maybe that artist is terrific at anatomy. Think of Craig Hamilton, who draws the most exquisite figures in comics. Maybe he doesn’t have the storytelling chops. A great editor can say, “Craig Hamilton, meet Peter Gross. Maybe Peter can do roughs and Craig can do pencils and Peter can do finishes.” What a team. A great editor has a vision and knows that if they’re asked to pitch a comic, that it can be first and foremost a brilliant story on paper, but have legs to actually work in multiple platforms, be it games, TV, film. That’s a great editor.

KS: If you don’t mind tooting your own horn, can you look back with perspective now—assuming you agree with my premise here— and see where you leveled up to being a great editor? Was it at Vertigo? Black Crown? I’m wondering where you feel you fully got your sea legs.

SB: I don’t want to sound arrogant because I’m humble, but I created my own systems of working at Comico. When someone says to you, “My two top people have moved to another company, would you like to be one half of a comic book company with Rick Taylor as art director?” That is the greatest gift you can be given in life, because that says someone trusts you at 22 years of age to get shit done. I wasn’t gonna let anyone down. Not my talent, not Phil Lasorda, not Rick. And we didn’t. The company went under, but that was not our fault. It was creditors.

I have to give my dad props because he taught me how to do business in a very honest, but very practical, way. I think I learned lots of great skills along the way, and I learned how to work in a big company by example, both good and bad. I think my vision of the kinds of stories I wanted to make was always there from when I went to film school. I knew that I liked British and European and French films. I knew I wasn’t part of the superhero scene. I was tired of order versus chaos. I was tired of good versus evil. And I liked city life, so I was seeing all of these weird off-off- Broadway shows and going to galleries that influenced the kind of modern culture I wanted to put through comics.

I think with each experience you learn new things. Black Crown kicked my butt in the best possible way in terms of putting a book together digitally. My husband deserves the credit for that because he is a tremendous graphic designer. When it came to us assembling the books and then creating our own identity, that is 200% Philip Bond. Having Philip as the creative director for Black Crown… well, it wouldn’t have looked anything like that if it wasn’t for him. Each experience has helped us define what I consider to be Off Register Press, which is a his-and-hers comics and design lab. I salute every one of the comics I worked on from 1988-2000 in my latest work, Fast Times, and it will continue in the third part of my “editing trilogy” because something I learned from Grant Morrison in working on The Invisibles is when you set out to create a trilogy, you can ignite a comic book revolution and change the world. That’s still my number one goal. With a killer soundtrack.

KS: Was there a time, or times, in your career where on paper you had all of the ingredients for what should be a successful comic and the cake just didn’t rise the way you thought it would? Or maybe it didn’t find the audience that you expected?

SB: That happens a lot. I have a whole folder of pitches that we call “the rejects.” Peter Gross and Mike Carey and I have so many pitches that were rejected after Lucifer, before they started The Unwritten, and we could not figure out what wasn’t working. Sometimes, your boss just doesn’t get your vision, fair enough; more often than not, projects don’t come together because the creative team that’s in your head doesn’t translate on paper. Another tip for people is, if you think an inker is going to work with a penciler, see what happens on paper. Sometimes, personalities don’t gel. Same with writers and artists. Get it on paper, get a sample. But nine times out of 10, there’s not enough marketing support for comics. It’s such a struggle. It’s been that way since Comico, it continues to be that way today. Companies have agendas. Big business is always promoting the “next big thing.” The hardest part about making comics is not just making them, but getting them into the right reader’s hands. The best way for that to happen, boots on the ground, word of mouth, and you cannot stop being your own fierce advocate. I don’t care if people think I’m a shameless self-promoter— if I don’t do it, I’m running the risk of actually being cut from the history pages.

KS: For a big music fan such as yourself, is there ever an opportunity to listen to music while you work these days?

SB: I cannot edit the front end of a book with any commotion. Front end of a book means pitch, outline, script, beat sheet, hardcore editing roughs. When I’m looking at the script and trying to approve the rough to approve the pencils, no go. My studio shares a wall with my son’s room. He is an avid gamer and there is nothing worse— being in a house with a physical therapist may be the only thing that was worse—but to hear my son play video games while I’m trying to edit? Not happening, I go to the library if we can’t come to a happy medium. I like to listen to music at the end of the job, maybe when I’m cleaning up my studio, maybe when I’m just kind of tearing up all the minutiae that is involved in making comics, because I’m still very much “build your dummy book.”

KS: Can you go into that for readers who may not know the term?

SB: Everything is about the piece of paper. I just finished four weeks of telling my class, “If you don’t have a stapler, buy a stapler. You cannot just rely on the screen.” I’ve seen too many people go to press with digital comics that you can’t read when they’re in print because they need the font to be enlarged; they’re not meant to be swiped on a phone. Print out your work. That’s my number one tip for anyone who wants to self-publish. For the love of God, print out your work, proofread it on paper, use a red pen, and before you go to press, have someone proofread your cover. Someone who doesn’t know what it’s supposed to say. Eight times out of 10, your logo’s not readable—you need to have contrast. Eight times out of 10, you have a typo, because it’s really hard to remember sometimes how to spell JM DeMatteis. Or it’s hard to remember your issue number if it’s not big on the cover. You’re going to be costing your company a lot of money if you’re not perfect.

KS: My last question is: Imagine a hypothetical Comic Book Hall of Fame for the very best of the medium, and you get to induct a title that you had nothing to do with creating. Graphic novel, series, American, international, any era… what’s getting your plaque?

SB: I have a tie. People to this day ask me “What is the comic that made you a lifer?” They assume it’s Fables, or they assume it’s The Sandman or Shade. It’s Stray Bullets by David Lapham. When I read issue number one, I knew I would not leave the comic book industry. What Lapham has been able to achieve from issue one to every time he puts down a pen… he is the epitome of a creator who has a vision, who can change the world through crime noir comics. He has redefined what can be done through crime comics. So, that’s one, Stray Bullets in its entirety.

The second one is Charles Burns’ trilogy, which is collected as Last Look: The Hive, X’ed Out, and Sugar Skull. It brought me to my knees. I was writing in the library a few summers ago, and I wasn’t really happy with my work. It was garbage and I gave myself a challenge that I was allowed to go into the graphic novel section, and pick one book to read before I was getting back to work. I took that first part of that book, read it, and then just got back up [for] the next part. I’m still in that library three hours later and my husband’s calling me and I’m whispering, “Come to the library.” And he’s like, “What’s wrong?” He thought maybe I was kidnapped. I said, “You have to come here. You have to read this book.” Now, being a wonderful husband, he trusts me. He sat down and he read Last Look. He knows I’m big on hyperbole, and so sometimes he thinks I’m blowing smoke, but I will tell you, he looked at me after he finished it, and he just nodded and said, “You’re right.” That’s Hall of Fame.

KS: You have a number of different projects in the pipeline, so please walk readers through what they should be on the lookout for and where they can find your work.

SB: One of my greatest claims to fame is being the esteemed editor on a book called Geezer, which is about a Brit pop band that almost made it, but not quite. Maybe you’ve never heard of them because maybe they really didn’t exist, but you’ll need to read the comic to find out. Number one was Kickstarted last year, and number two is Kickstarting by the time your readers see this. The artist is my favorite comic book artist on the planet, Philip Bond, who I married and who doesn’t mind that I edit him once in a while. I’m also lettering the book; I taught myself how to letter a number of years ago and I’m addicted. Geezer is a seven-inch comic book. We are actually doing five issues, then once we have those five issues finished, we hope to Kickstart a full-color, 12-inch version, a hardcover coffee table book. This book is definitely a must-have for anyone who likes music or comics or music in comics.

It is very dangerous to write, edit, design, art direct, and also do production, so on my books Filth & Grammar and Fast Times, I actually have an editor—Will Potter, who is the writer of Geezer. One of the nice things about self-publishing is sometimes you pay each other, other times you pay each other compliments, and then other times you pay each other in exchange. Will and I edit each other and it’s a wonderful thing; we have similar instincts and yet we trust each other to be brutal. He’s way more brutal on paper than he is in person because he’s English. and he always feels like he’ll hurt my feelings. I’m just brutal, period. [laughter] So, I tell him off face-to-face sometimes. But we have a great working relationship.

For my personal work, I’m going to be be Kickstarting a book called Death by Misadventure. It’s a lot of stuff that didn’t fit in Fast Times because during the pandemic when everything in comics closed down, I pretty much got a group of friends together to put out some pandemic projects, and I just wanted to continue working with some of these great artists. I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t afford to pay anyone to write and draw, so I decided to roll up my sleeves and I tried my hand at writing.

I have to tell you, writing comics is way more fun than writing prose. I find my cadence to be annoying when I write prose. My tip to people who want to write is, write comics because not all of your words will see print. So, many of your words are in the art direction, and an artist will make your words look so much better. If you tend to be long-winded, like I am, honing your own prose can be tough. It’s never a problem to slice anyone else’s prose to red ribbons.

My book, Fast Times in Comic Book Editing, which is part two of the trilogy, will be in my hands in late April/early May, and I will be fulfilling my Kickstarter backers first so sometime in late May when I get all of the packages out, I will put the remaining copies on Offregister.press, which is where you can find all of the personal work by my husband and I.

The final part of the trilogy is I-Doppelganger: The Comic Book Editor in the 21st Century. That will cover all my work from the year 2000 to present day. I’ll be looking at the tropes that we find in comics and how we can turn them around, come at them from different angles. Hopefully, it will be enjoyable, because it’s not only a look at my own body of work, but a way of inviting every reader to look at the comic as a bullet journal, to actually roll up their own sleeves, and try their hand right next to me—sort of like riding shotgun.

Parting words? Here are ten: The best time to make comics is now. Viva comix!

Find the Kickstarter page for Geezer #2 here.

This interview was edited for length.