It was 50 years ago today that audiences were transported back in time a million years to a watering hole on the African desert, where two rival hominids clashed with deadly results in the shadow of a black monolith. Directed by Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey has become one of the most revered films in the history of cinema and has influenced many of our contemporary science fiction directors today. Fanbase Press honors the 50th anniversary and celebrates the fandoms surrounding this film.

Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, has been an undisputed milestone in cinema. The film is noted for its many accomplishments: its use of music, its famous match cut, prophetic anticipation of technology, artistic narratives, and, of course, its special effects. Kubrick’s film set an unprecedented leap for the depiction of realism in an outer space film – immaculately detailed space stations, space shuttles, astronauts in EVA, and so on – all realized with special effects that netted Kubrick’s only Oscar win.

Conversely, moving from the world of auteur filmmaking to that of Italian genre cinema, director Antonio Margheriti had spent the ’60s honing his special effects craft via the usage of miniatures and models. Aside from Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965) and Paolo Heusch’s The Day the Sky Exploded (1958), Margheriti practically single-handedly blazed a trail in Italian outer space/sci-fi film making. Margheriti contributions to the genre include his directorial debut, Assignment: Outer Space (1960), Battle of the Worlds (1961), and the four films that make up the Gamma One Quadrilogy: Wild, Wild Planet (1965), War of the Planets (1965), War Between the Planets (1965), and Snow Devils (1965).

Due to Margheriti’s experience with shooting outer space scenes, especially those with space stations and astronauts in zero G, there were rumors that Margheriti had a hand in 2001: A Space Odyssey. In an interview with Video Watchdog, Margheriti clarified his involvement with Kubrick’s film:

“..I didn’t do anything. Somebody from the production who was a friend of mine called me, I went to London, and we spoke about the project, because I was one of the few directors who had any experience with this kind of story. … But I did visit the studio, I did meet Stanley Kubrick and the special effects guy Douglas Trumbull … I just discussed some things and gave my advice on certain aspects.” (Video Watchdog #28, page 53)

While Margheriti’s involvement with 2001 was minimal and relegated to giving advice, it is uncanny to compare shots from some of the films in Margheriti’s Gamma One Quadrilogy to shots in 2001. The difference in the quality of models used between Margheriti’s films and Kubrick’s is obvious, yet the similarities in mise en scene, as well as the “heart” of what both directors are trying to capture, are profound. Both directors seemed to share the same vision and accomplished similar sequences in their respective films, though Margheriti with a substantially reduced budget.

For example, take the image at the beginning of this article that compares two space station docking sequences. The top image is from 2001 and shows a Pan Am space ship flying toward the Space Station V while the bottom image is from Margheriti’s Snow Devils (though the sequence was re-used in the other Gamma One films) and shows a space ship flying toward the Gamma One space station. The space stations in both films are modeled off Wernher von Braun’s concept of the rotating wheel space station, and both shots follow the same mise en scene: the spaceship approached the space station from the right. The big difference in the frames is the presence of Earth in Kubrick’s shot, greatly grounding not only the realism of the scene, but the scale, as well. Though Margheriti’s incarnation of the station and the spaceship aren’t fooling anybody, the sequence is still expertly executed.

Writing for the now defunct SF Site, Gary Westfahl makes his own Margheriti-Kubrick-2001 speculation:

“And while I have no definitive information about Margheriti’s actual, uncredited contributions to that landmark film, he was probably summoned to assist with the scenes of Bowman and Poole outside the Discovery, the part of 2001 that most forcefully displays Margheriti’s influence.” (https://www.sfsite.com/gary/marg01.htm)

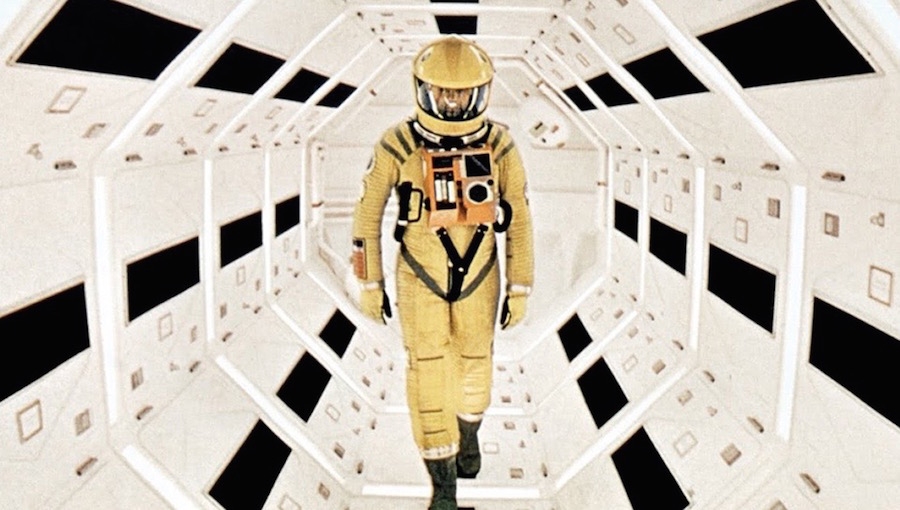

A comparison of a frame from 2001 (top) showing Bowman and Poole diagnosing the antenna control device and a scene from Margheriti’s War Between the Planets (bottom) showing astronauts leaving their space ship for a space station displays both directors’ handling of zero G scenes:

Again, the mise en scene is similar, with the destination spaceship/station on the left and an astronaut(s) on the right, flying toward it. Both frames are also lit the same way (from the front), mimicking outer space realism that light would be coming from a single source. Margheriti’s films are notorious for their blatantly visible wire framework for the zero G sequences, but as with the space station docking sequence, his zero G sequences are realized as proficiently as possible with the budget and materials on hand.

Quality of miniatures aside, it’s not far fetched to think that perhaps some of Margheriti’s advice to the 2001 production team was taken into consideration. Both Kubrick and Margheriti were masters of their respective filmmaking and special effects crafts, realizing grand visions of the future. Though Margheriti’s association to 2001 is tenuous at best, it’s still an interesting curio in regard to Kubrick’s film.

Nicholas Diak is a pop culture scholar of industrial and synthwave music, Italian genre films, peplum films, and H. P. Lovecraft studies. He contributes essays to various anthologies, journals, and pop culture websites. He is the editor of the anthology, The New Peplum: Essays on Sword and Sandal Films and Television Programs Since the 1990s. He can be found at nickdiak.com.