For the past ten years, Classic Comics Press has been collecting and republishing American comic strips, many originating from newspapers from decades past. Their flagship line has been Leonard Starr’s Mary Perkins, On Stage, but the publisher has republished many other comic series as well, such as Stan Drake’s The Heart of Juliet Jones and Frank Godwin’s Rusty Riley, both that ran during the 1950s.

While Classic Comics Press has focused on American comics, they recently released a European comic that was created by the Americans Starr and Drake, Kelly Green: The Complete Collection. Originally published by the French publisher Dargaud in the early to mid-1980s for the European market, the choice for Classic Comics Press to republish Kelly Green after almost thirty years is an appropriate move to complement their other Starr and Drake offerings. Starr, a veteran of many years working for EC Comics in the 1940s and DC in the 1950s, is mostly renowned for creating Mary Perkins, On Stage in the 1950s and for reviving Little Orphan Annie in 1979. Drake, also a seasoned veteran, would eventually take over illustration duties on Blondie in the 1980s.

Kelly Green: The Complete Collection bundles all five graphic novels of the series into one omnibus: “The Go-Between,” “One, Two, Three, …Die!,” “The Million Dollar Hit,” “The Blood Tapes,” and “The Comic Con Heist.” The last story, “The Comic Con Heist,” is of particular importance since it had never been published in English before, making this collection the first opportunity for American audiences to read the final Kelly Green story.

The series revolves around the titular Kelly Green, recently widowed after her husband, a police officer, is killed during a police raid. A motley crew of ex-criminals who were reformed by her husband take the guardian angel role to Green, but also expose her to the criminal world. In the process she becomes a go-between, the intermediary in blackmail schemes between the blackmailer and the victims. Green’s role as a go-between is rarely straight forward as she becomes personally invested in each ransom transaction, often working to uncover the identities of the blackmailing party and solving the underlying mystery at the heart of each story.

As a neo-noir, the overall stories may tread familiar ground, but with Green as the lead and situated in the more modern setting of the 1980s as compared to the 40s and 50s, the plots come off original and fairly interesting. “The Go-Between” focuses on Green coping with the loss of her husband while at the same time uncovering the circumstances that led to him being killed while on duty. “One, Two, Three, …Die!” sees Kelly dealing with a kidnapped dog and a dysfunctional wealthy family. “The Million Dollar Hit” has Kelly involved in the world of oil tycoons, politicians, and wilderness survival that may take more than a few cues from the film Alive. In “The Blood Tapes,” the last story that was made available to English speakers, Kelly is trying to recover the master tapes of a popular musician, but winds up working with the mafia and a mobster who bears uncanny resemblance to her deceased husband. In the final story, “The Comic Con Heist,” Kelly works to recover a set of original comic art while an unhinged police officer, who does not play by any rules, goes on a violent rampage against Comic-Con guests.

In the first story, “The Go-Between,” there is some smartly executed detective work. Astute readers who pay attention to the details present in the comic’s panels will be able to deduce the story’s culprit on their own. Sadly, this gimmick only happens in the “The Go-Between” as the rest of the stories in the collection reveal the truth only when Green herself presents it. Rather than detective work, the stories become a guessing game of who is out to get whom, relying more on Scooby Doo logic of the last new character standing is the guilty party. Because of this aspect, the Kelly Green comics are less detective work, despite Green assuming the mantle, and more linear neo-noir stories.

Being a woman-centric character comic, there are many aspects of Kelly Green that would resonate with today’s readers who are more conscience about how women are portrayed in the medium. She is both resourceful and fairly autonomous on her different ransom escapades; however, there is an implied, behind-the-scenes safety net in the form of Spats, Meathooks, and Jimmy, the three criminals reformed by her husband. Though they provide Kelly with her jobs, information, and advice, they can also be sensed off panel, ready to jump in if Kelly becomes a damsel in distress. Luckily, only once in the series, during “The Million Dollar Hit,” does Green become a damsel in distress, but she is able to use her own wits and agility to escape her captors.

As a female noir character, Green is interesting in that she straddles the boundary between femme fatale and femme fragile. Green conceals weapons and shows proficiency with physical combat but never embraces the full seduction aspect of a femme fatale. During the Kelly Green run, there are numerous scenes of Green in various states of undress and displayed in cheesecake poses, but only once during “One, Two, Three, …Die!” does she actively attempt to charm and seduce a character. The majority of all other instances of Green in revealing shots are when she is alone; she is being used to titillate the reader, but not another character.

Being a product of the early 1980s, it is unavoidable that many elements of Kelly Green have not aged well. Technology notwithstanding, cultural attitudes present during the run of Kelly Green have greatly shifted in the three decades since. For instance, the depiction of gay men goes to two polar extremes between two different characters. One character is depicted in the highly flamboyant and helpful stereotype. Another is portrayed viewing his homosexuality as shameful and embarrassing, and going to murderous extremes to hide it. It is obvious Starr is a little out of his element writing these characters, relying more on Paul Lynde stereotypes and the general negative perception of gays during the AIDS panic of the 1980s. The portrayals are not derogatory, but they are not flattering either.

For comic book fans the most shocking instance of aging is the depiction of San Diego Comic-Con. Present-day Comic-Con attendees can only dream for the “long lines” depicted in “The Comic Con Heist” when compared to today’s crowds. Comic-Con, as depicted in Kelly Green, truly is about the medium proper; the story acts as a love letter from Drake and Starr for sequential art, with a few murdered cosplayers thrown in for good measure.

Classic Comics Press gives Kelly Green: The Complete Collection a Criterion treatment with an essay from 1983 based on interviews done with Drake and Star, an essay by illustrator Steven Ray Austin who recalls his time working on Kelly Green drawing backgrounds, and an afterward by Charles Pelto of Classic Comics Press who talks about re-lettering and restoring the original art by removing the color from the out-of-print Dargaud editions. There is also an appendix gallery of cover art, promotional material, and a story board to final product comparison.

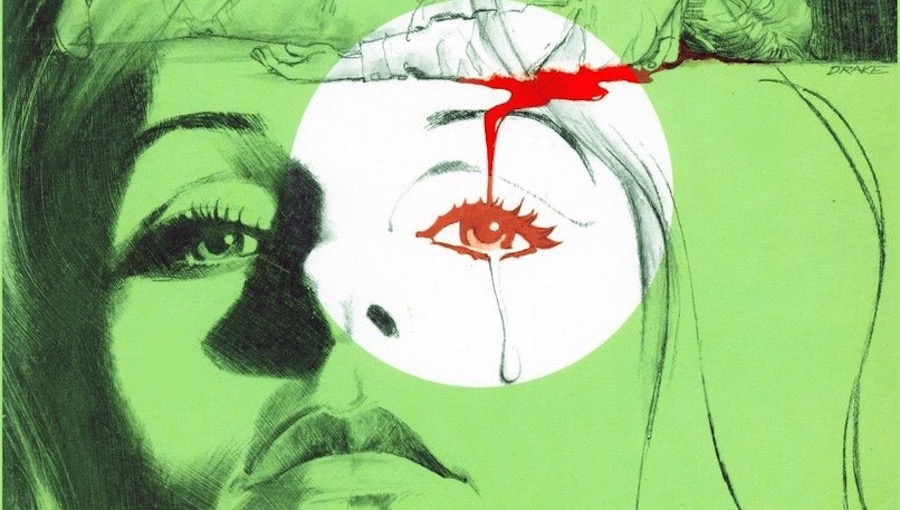

The decision to remove the color work is a somewhat mixed bag. Per the inside dust jacket, this reverse restoration was done to underscore Drake’s line work, which it certainly accomplishes. The artwork in Kelly Green is no less than fantastic. In contrast, the original publication of Kelly Green by Dargaud was in color, so by removing the color from these versions, the original presentation is lost. While this gets into the realm of what is the best “true” version (original authors’ or original publisher’s), it should be pointed out that by reading this reprinted black-and-white incarnation, without being overtly told so by the various essays, a reader would have no idea that Green’s hair is actually red.

Regardless of this decision, the end result is that Kelly Green: The Complete Collection is the definitive omnibus of the Kelly Green stories. Meticulously compiled and preserved, the book gives the Kelly Green run a brand new life. The series may be a minor footnote in both Drake and Starr’s careers, but it deserves reconsideration and reappraisal. Perhaps a little bit of a relic of its time, the true highlight of Kelly Green is Kelly Green herself. While the plots may not be the most original, Green certainly is. Written against the type of both yesteryear and today, Green is both a fleshed out and fully realized female protagonist. Comic creators looking to the past for inspiration in developing their own female characters should look to Kelly Green.