Almost eight decades after his passing, the influence of H.P. Lovecraft on contemporary speculative fiction remains profound. With many of his works in the public domain, other writers have sought to continue his legacy by either writing their own stories in a Lovecraftian vein, or by taking Lovecraft’s original source material and building on it with successor stories. Since the publishing barrier has been set extremely low due to the accessibility and affordability of self-publishing, a literary landscape has sprung up, saturated with Lovecraftian stories penned by both proficient writers and imitators. Almost any speculative writer can lay claim that they write in the Lovecraft fashion; hence, readers must be able to sift through the sea of stories of dubious merit to find interesting and competently written tales of cosmic horror.

In order to stand out in this landscape, many small press publishers of Lovecraft-inspired short story anthologies turn to unique themes to distinguish their output. For example, Simian Publishing’s anthology Apotheosis: Stories of Human Survival After the Rise of the Elder Gods focuses on stories in a world in which Cthulhu and his ilk have already risen from their slumber, while Dark Regions Press’ World War Cthulhu: A Collection of Lovecraftian War Stories incorporates eldritch horrors into military fiction.

The Whispers from the Abyss anthology line from 01 Publishing takes a different approach to distinguish itself from other collections. Rather than relying on a particular theme, Whispers from the Abyss instead focuses on readers on the go – commuters, bus riders, and carpoolers – generally, the folks who have a few rare moments to spare during their day. The stories are tailored to this demographic in that they are fairly short, designed to be quickly consumed while being as fulfilling as a longer story.

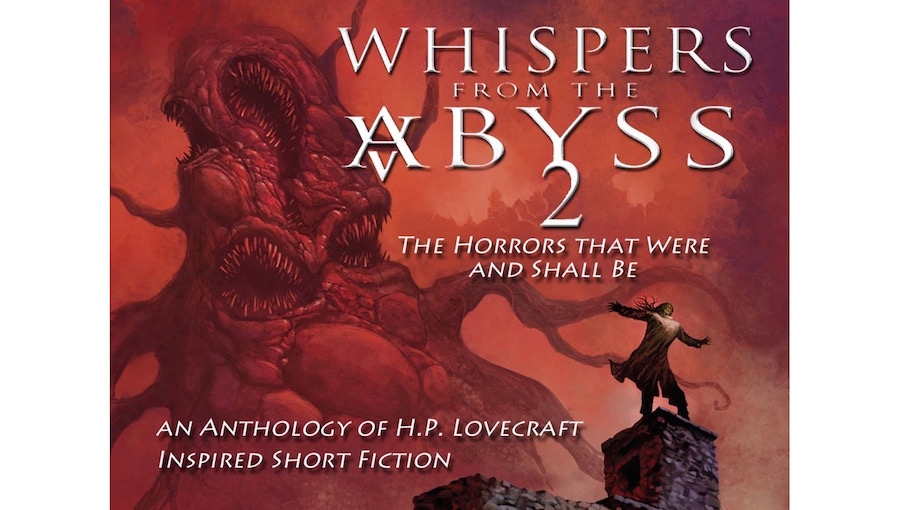

Whispers from the Abyss Volume 2 is the newest entry in this anthology line. Previously released as an electronic-only version, the collection recently had a successful Kickstarter campaign to realize a print incarnation. The anthology is composed of twenty-five stories, with renowned genre authors such as Cody Goodfellow, John Palisano, and A.C. Wise providing marquee value. The stories range from humorous to serious cosmic horror, sequels to Lovecraft’s stories, and traditional narratives to experimental narratives.

With the reduced word count limitation, authors are not afforded extra the real estate that they would otherwise use to bolster character development and additional exposition. For the most part, the authors in Whispers Volume 2 economize fairly well, and their stories are competently executed and entertaining.

The issue with the majority of the stories in the anthology is a shared problem with other authors tapping into the Lovecraft formula, and that is the near-strict adherence and verbatim trope lifting from the original texts to the point of being a deterrence in their new stories. For example, in the original Lovecraft story “The Call of Cthulhu,” the island of R’lyeh is described in paradoxical terms such as acute angles behaving as if they were obtuse and geological features not being in correct positions in relation to each other. The first story in Whispers Volume 2, A.C. Wise’s “We Are Not These Bodies, Strung Between the Stars” is heavily constructed around similar types of paradoxes and descriptive contradictions. The narrative is built on sentences such as “I remember. Too many Limbs. Or not enough,” “We’ve been gone a millions years and only a day,” and “Time is broken. And because it is broken, it has always been broken.” The story is bogged down by the author’s attempts to portray the unportrayable and the end result is a near-incomprehensible tale.

Stories such as John C. Foster’s “His Carnivorous Regard” and Sarah Hans’ “Shadows of the Darkest Jade” temper the hyperbolic writing, creating concise, easy-to-follow plots with clear-cut characters and unfolding action. “His Carnivorous Regard” takes place on a space station and has an Event Horizon feel to it, while “Shadows of the Darkest Jade” is about two monks traversing the lands to spread their message who wander into a village where nefarious rituals are happening. Both stories are executed well, but both apply the same trope of holding back the goods, such as not showing the monster, deity, or some other unfathomable entity at their respective climatic moments.

It is not really a deal breaker per se, since the “less is more” and “readers should use their imagination approach” are dominant mantras in horror writing, and many of Lovecraft’s own stories employed these devices. For example, at the end of At the Mountains of Madness, the narrator never takes a look at the monster chasing him, and thus the reader has to fill in the blanks themselves as to what it may look like. The situation has greatly changed since this time in that there are now several decades worth of writers and companies like Chaosium that have expanded the Lovecraft universe and its bestiary by leaps and bounds. A stage has been reached that so much of the unknown presented back in Lovecraft’s day has been fleshed out and is quite well known and grasped today. Many Lovecraftian-inspired stories, not just from Whispers Volume 2 but from a majority of other writings, have continued to tap into this trope, oblivious that it is now a worn cliché rather than a device that advances good story telling. Another way to put it, these stories put their efforts into not showing things that readers have already seen instead of showing things that readers have never seen.

The most interesting contemporary Lovecraftian stories are the ones that tap into the latter and, thankfully, there are a handful of such tales in Whispers Volume 2. The final entry in the anthology, Martin James Hunter’s “The Dreadful Machine,” is easily the best story of the lot, not just because it is well written (It is.), but because it both shows and tells. The story revolves around a mysterious machine that has to be constantly maintained. In less-skilled hands, a writer of this story would have vaguely alluded to what was being inputted into the machine and end the story on that note, which would been in alignment with traditional Lovecraftian hegemony. Hunter subverts this by not only revealing what is going into the machine, but goes a step further into why the machine does what it does. This reveal is where the true horror of the story lies, and it is infinitely more engrossing and impactful than noncommittal half allusions other stories would use.

John Palisano’s “Lucky Chuck Takes the Sunshine Express” is another successfully implemented story in Whispers Volume 2, though as its title implies, it veers to the comedy side rather than outright horror. With a promise of a free trip to Vegas, Chuck takes the titular Sunshine Express straight into a modern-day Cthulhu hippy cult. In this story, the emerging monster and associated horrors are fully described, but the interesting subversion is with Chuck himself. The character is not a typical Lovecratian protagonist; he does not succumb to madness nor is he imparted with reality-bending cosmic knowledge through his ordeal. He is enough of a Shaggy/Scooby Doo-type character that readers relate to him differently. He is a lazy coward who has lecherous thoughts about the story’s various attractive ladies, and despite his encounter with unimaginable cosmic horror, he remains steadfast to bumming as much free food as possible on his trip to Sin City.

A few of the stories in Whispers Volume 2 try their hands at conveying their stories via other literary formats. Deborah Walker’s “Baby Rhyme Time: Youngsters Enjoy Initiation at Innsmouth Public Library” is written as a newspaper article while Richard Lee Byer’s “Kickstarter” is written as if it where the description of a crowdfunding campaign. The best one of these alternative formats is Kevin Wetmore’s “Notebook Concerning the Class Struggle in Dunwich, Found in the Ruins of a Construction Site” which is told through diary entries written back in the 1980s but only recently discovered. Much like Palisano’s “Lucky Chuck” the best asset of Wetmore’s story is its narrator who goes against the Lovecraft grain. He is an insufferable, privileged Miskatonic student who seeks to build houses to support low-income families in the swamps near Dunwich. Obviously, his plan does not go well. While most diary entries might be filled with the author’s thoughts of horror and boogeymen-things happening around him, the narrator in “Notebook” instead stays on his socialist high horse even in moments that abject terror is the traditionally expected response. This juxtaposition creates a weird comedy-horror hybrid that is pulled off well, much akin to slasher films in which there are a handful of characters that the viewers are eager to have disposed of.

Whispers of the Abyss Volume 2 is successful at delivering Lovecraft-inspired stories on a short scale. The intended audience may be folks on the go, but a wider audience will definitely appreciate them. The majority of the stories are competently written, but aside from a handful of exceptions, they are not necessarily original. The stories in Whispers Volume 2 that do stray from the old formula are the definite gems of the anthology, and it is hoped that even more stories of this type show up in Whispers Volume 3.